Another Round of COVID Confusion

You heard: Breakthrough infections are uncommon.

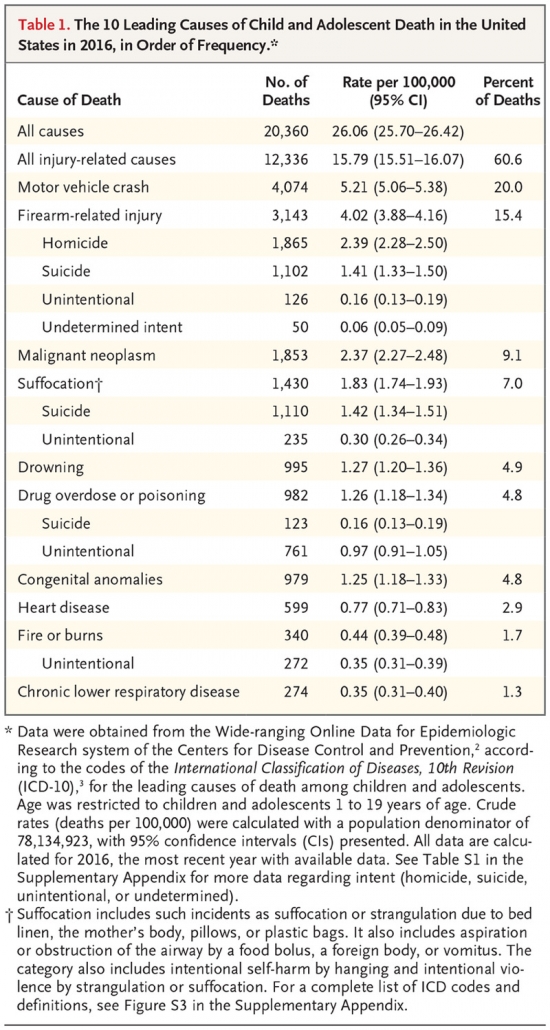

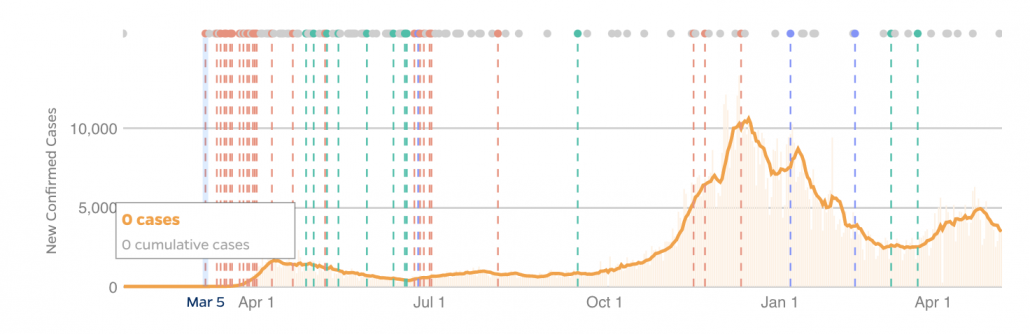

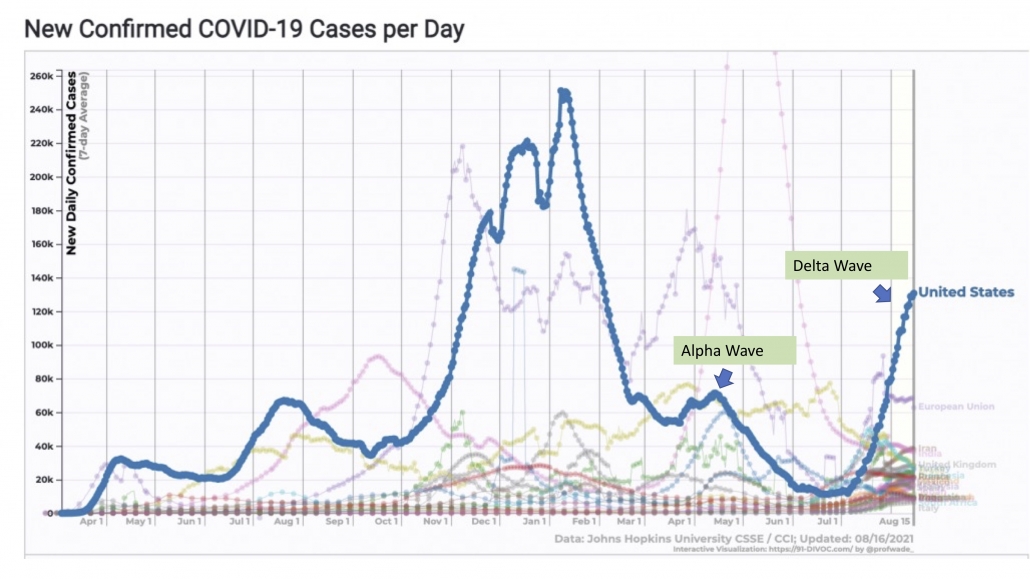

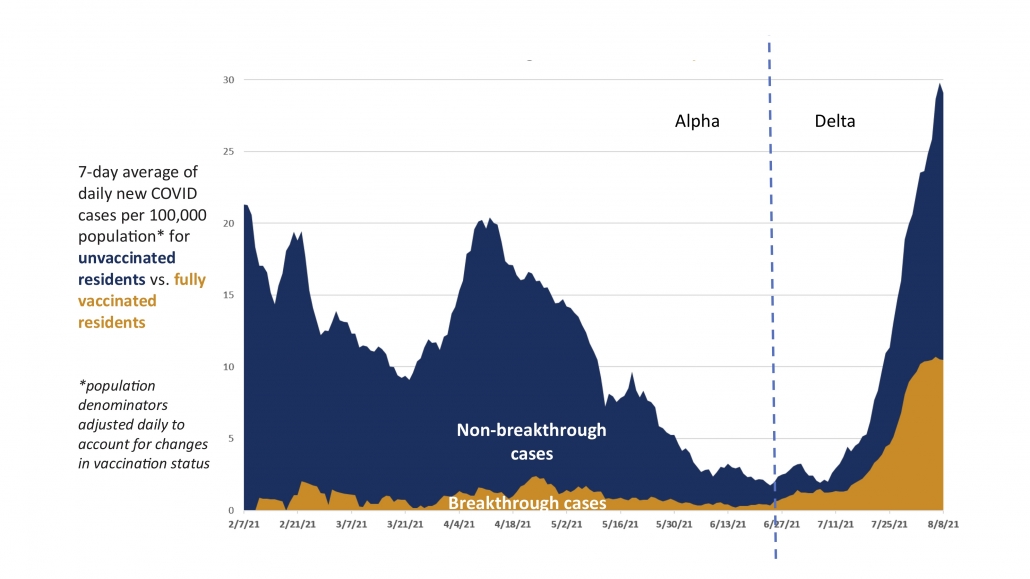

What that means: Breakthrough infections are uncommon when you look at the totality of data spanning from when vaccines began to be rolled out in December 2020. The New York Times and other papers often cite a Kaiser Family Foundation report that states Almost all (more than 9 in 10) COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths have occurred among people who are unvaccinated or not yet fully vaccinated, in those states reporting breakthrough data (see Figure 2). But data from last spring does not necessarily capture the current picture.

We expect breakthrough infections to become more frequent as more Americans get vaccinated.

We expect breakthrough infections to become more frequent as COVID cases rise, driven by explosive growth in unvaccinated people.

Moreover, there appears to be a higher rate of breakthrough cases since Delta variants ripped across the country this summer, even controlling for the larger population of vaccinated people compared to last spring. See the figure below from Dane County, Wisconsin (yes, it would be useful to have this kind of figure for nationwide data but America has crippling data collection problems). The 7-day rate of infection for unvaccinated residents is almost 3x times higher than fully vaccinated residents (29.1 versus 10.5 per 100,000), showing that vaccines do work. Still, with 68% of the population vaccinated (including 79% of eligible people), this still means many of the cases will be breakthrough (43% breakthrough/57% unvaccinated).

But it’s important not to conflate rising breakthrough cases with reduced effectiveness of the vaccine. It’s always compared to what?

You heard: Protection from the vaccine is waning and I need a third shot booster.

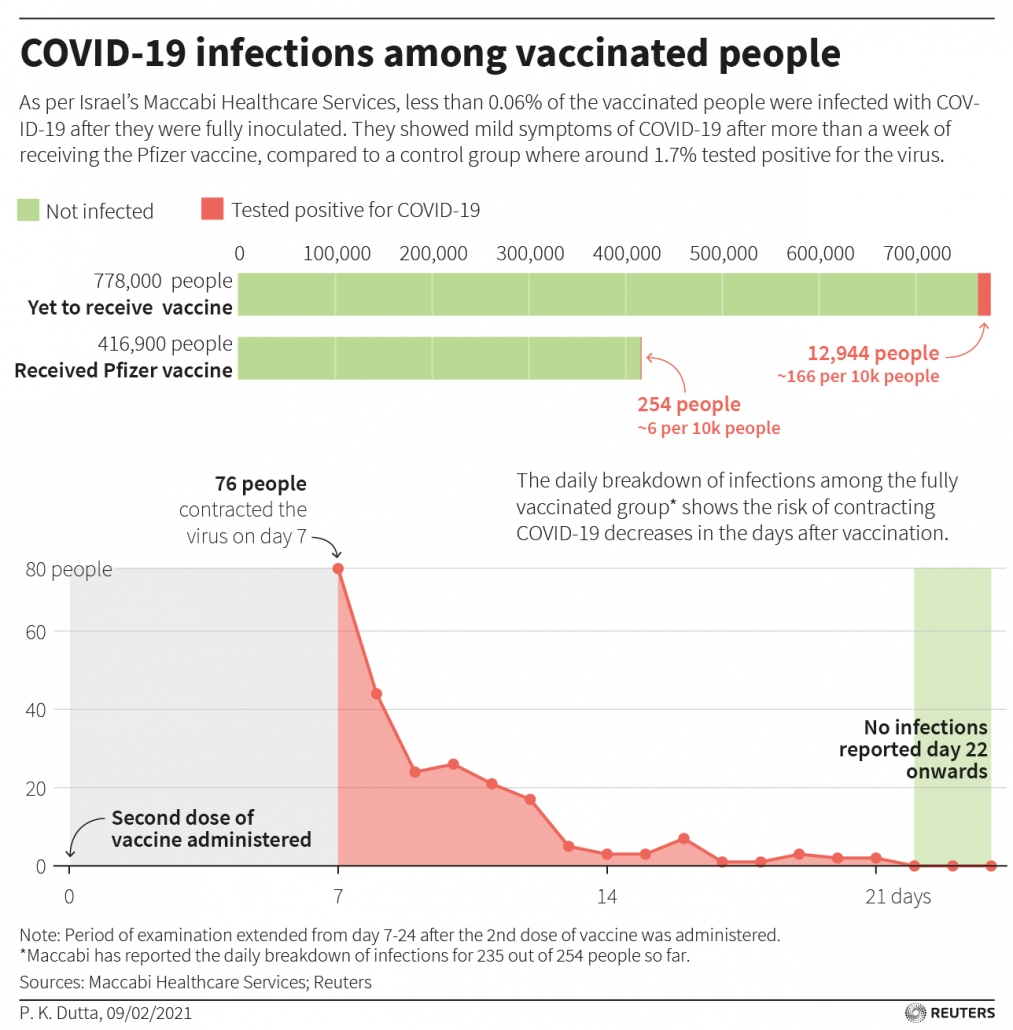

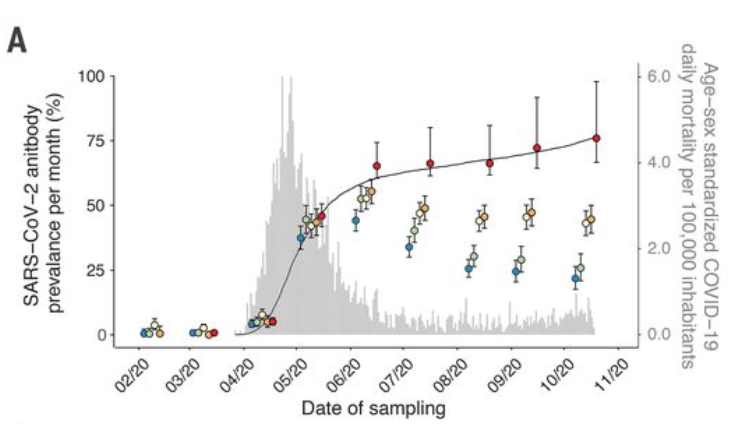

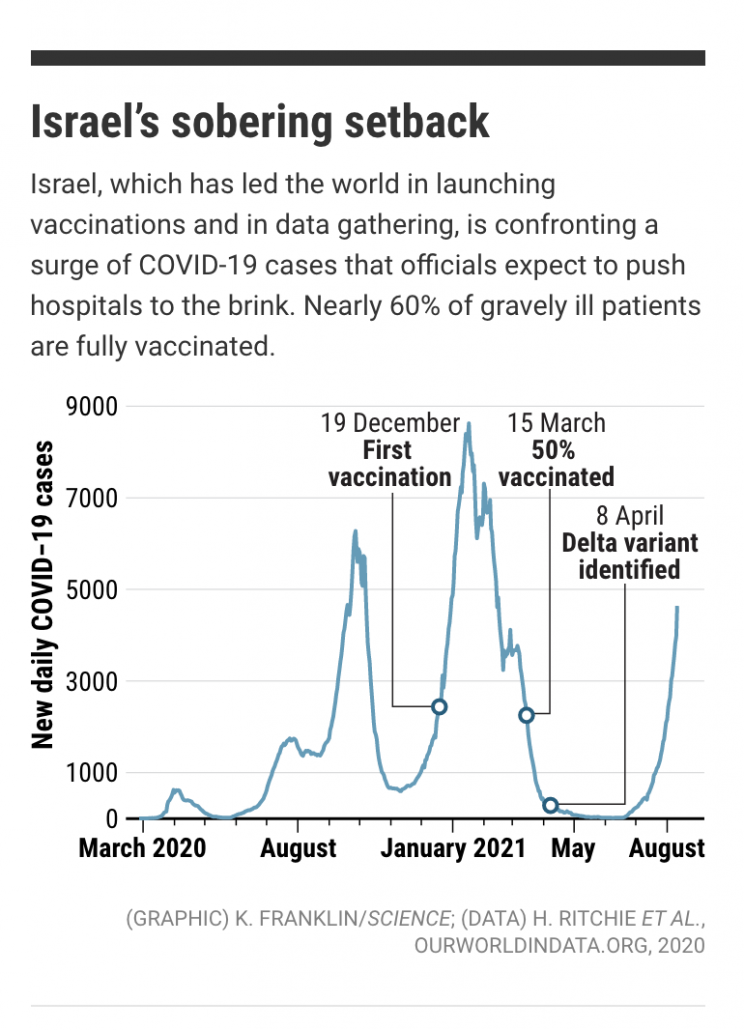

What that means: Israel was supposed to be the poster child for an effective vaccine campaign that beat back COVID. The country not only received an early supply of Pfizer vaccine but benefits from a highly monitored health system to track the vaccine’s impact. Over 78% of the eligible population was vaccinated by July 1, 2021 and COVID deaths had sunk to zero for the first time since the start of the pandemic. Data was showing that COVID-19 vaccines were not only effective in preventing hospitalization and death, but also in blocking infection and transmission. The feared spring wave of UK Alpha variants never materialized in Israel or the US the way it did in European countries with lower vaccine rates. Vaccine offered salvation. Until it didn’t.

There has been a lot of handwringing about vaccines not working anymore. It sounds bad when of the 515 patients currently hospitalized with severe cases in Israel nearly 60% are vaccinated. Media outlets have quoted this figure to suggest that vaccine effectiveness has waned and third shot boosters are needed.

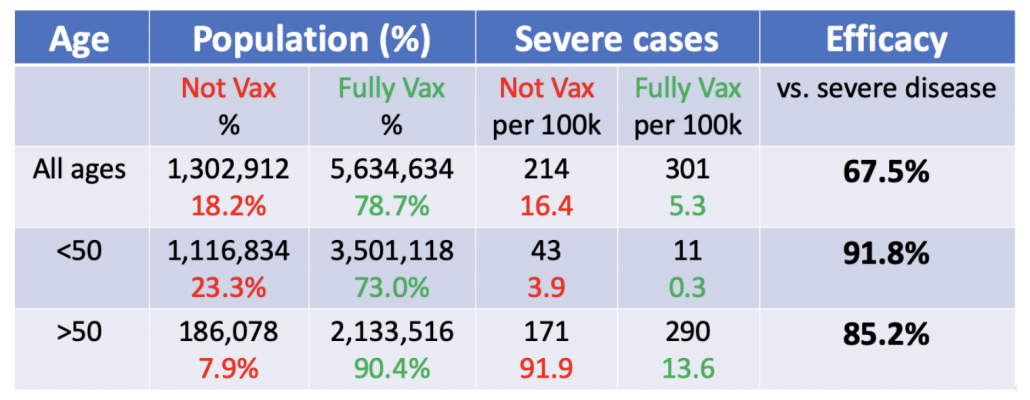

A helpful COVID-19 Data Science post explains step-by-step how appropriately stratifying by age can change the interpretation of vaccine effectiveness (VE) data. If you’re reading oversimplified VE percentages in the media that are not age-stratified, you should just ignore them. Here’s why:

- Nearly all older people were vaccinated (>90% of residents >50yr) while the vast majority of unvaccinated are younger people (>85% of unvaccinated <50yr)

- Older people are orders of magnitude more likely to be hospitalized than young people. Those >50yr are >20x more likely to be hospitalized compared to <50yr and for 90+ are the difference is >1600x more. These are enormous confounders.

If you estimate VE without taking into account age you get 67.5%, which means 2/3 of severe cases are prevented by vaccine. Pretty good, but not as good as the previously touted 90-95% range.

But….if you take into consideration the fact that more vaccinated people are old and much more likely to get hospitalized in the first place (91.9 versus 3.9 in unvaccinated group = 23x more likely) things start to look a lot better. VE for younger people is 91% (1 – 0.3/3.9) and VE for older than 50 is 85% (1 – 13.6/91.9). VE is expected to be lower for older people who don’t mount as good immune responses. In fact, VE might drop quite a bit for 70+ and 80+ if you further stratify by age (bumping up the VE for 50-59). But overall these are good numbers and the vaccine is performing well against Delta in protecting people against severe disease. It may seem statistically impossible that 85% VE + 91% VE = 67% VE (combined), but that just shows how important the age-stratification is.

How well the vaccine protects against mild infection with Delta is another question that requires deeper data.

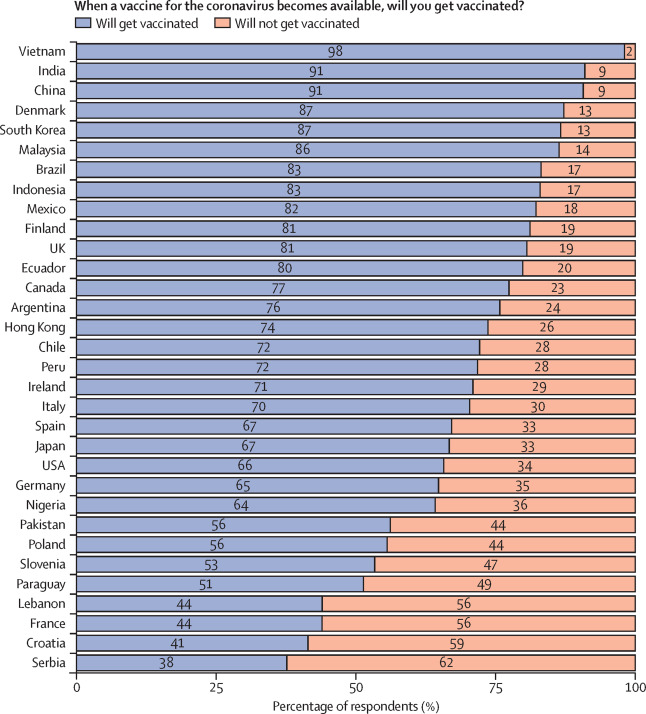

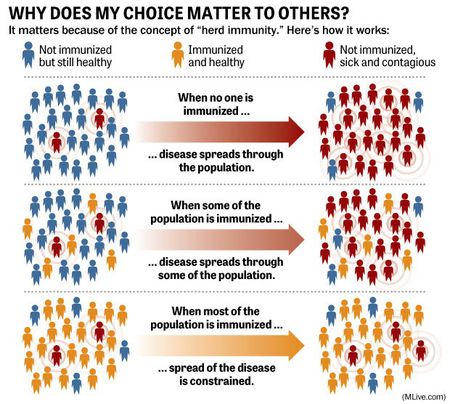

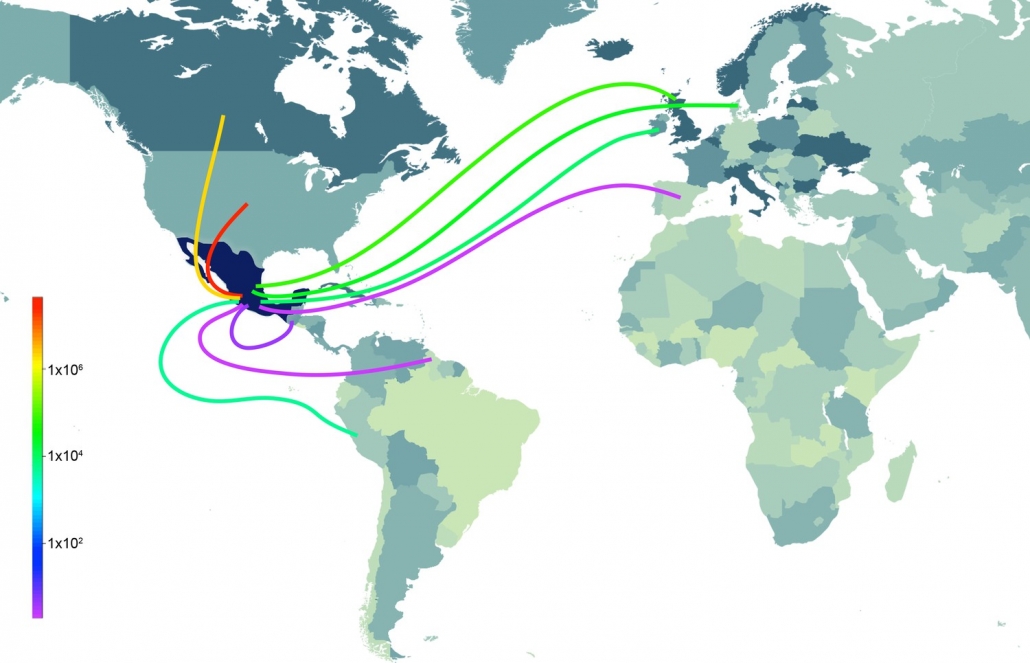

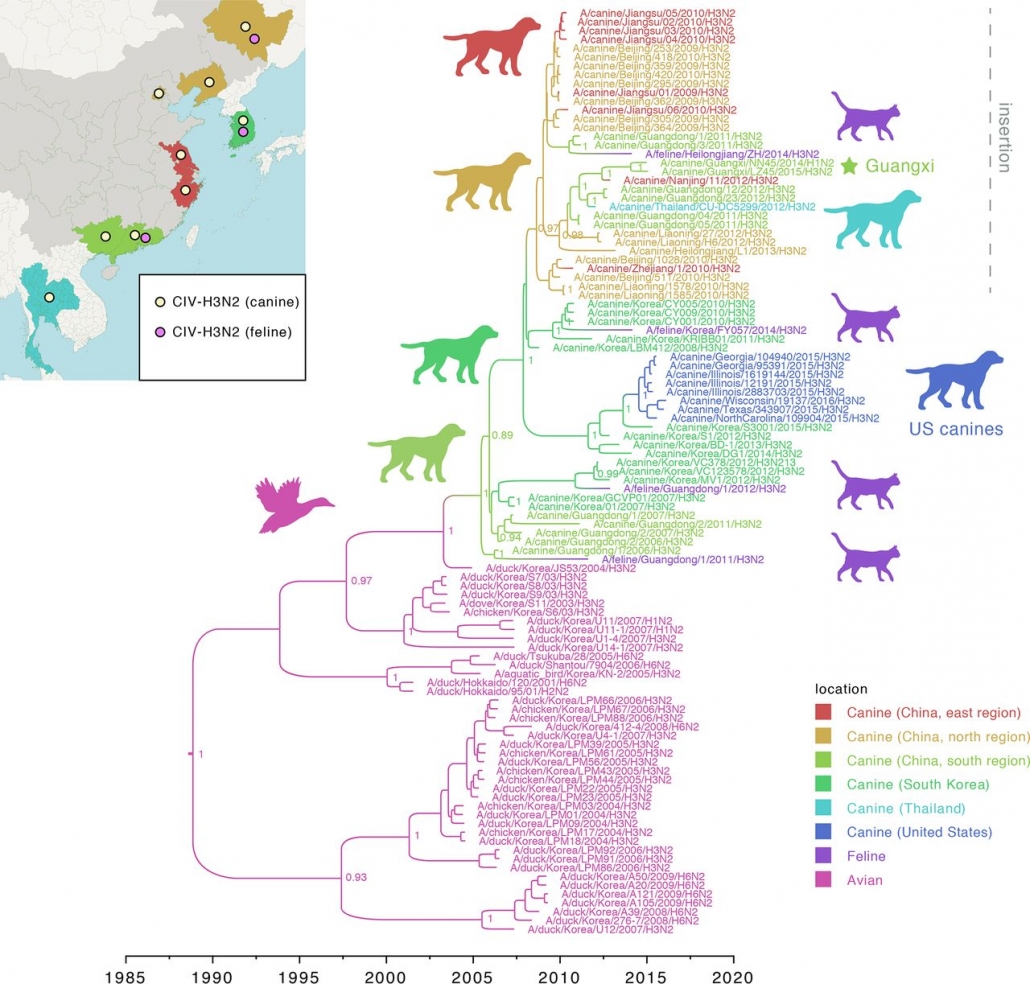

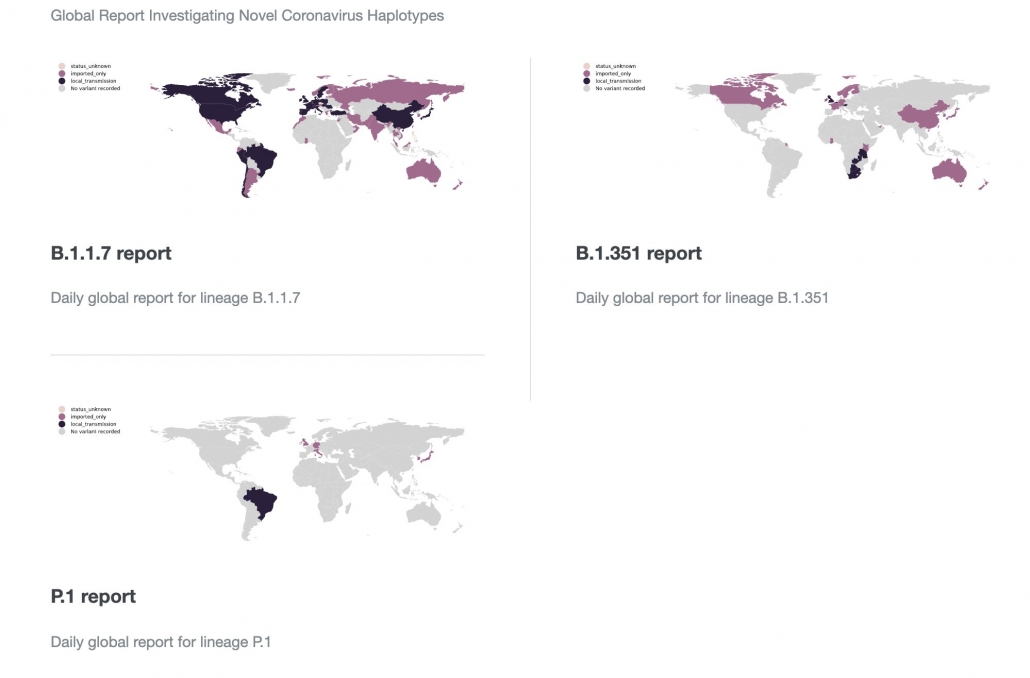

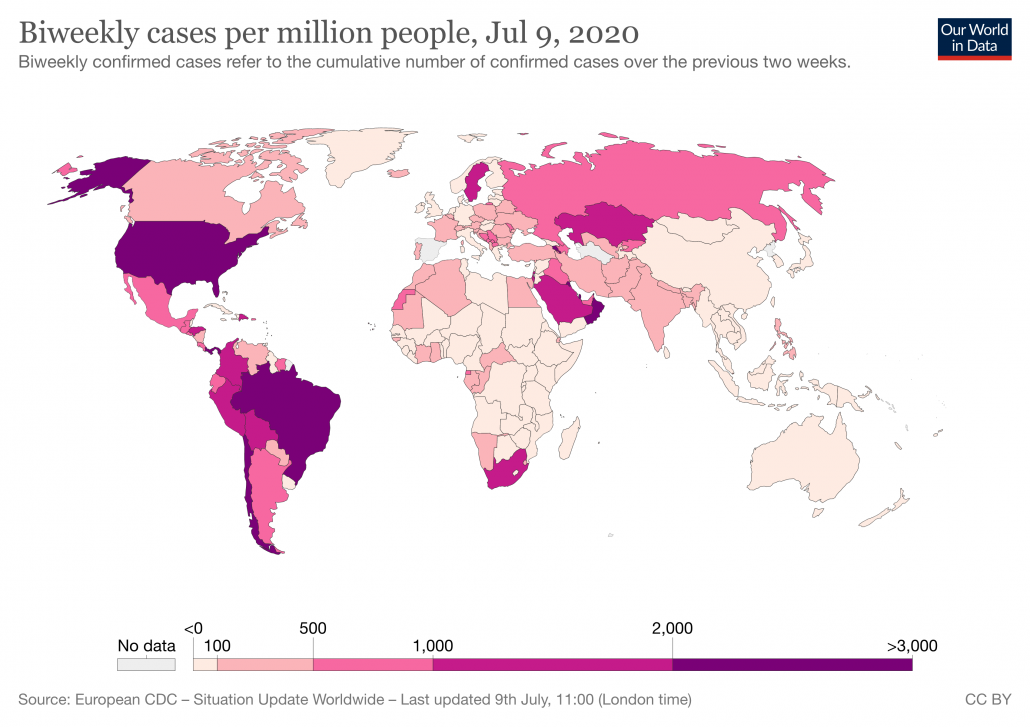

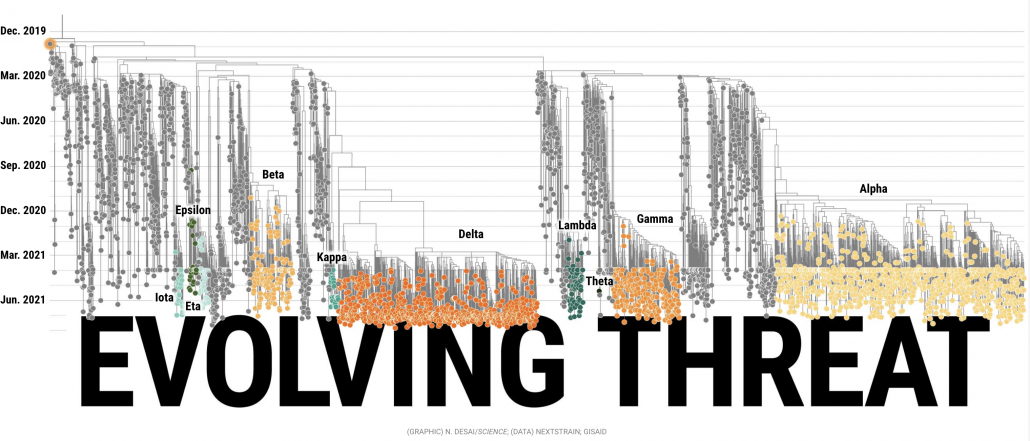

Later in September the FDA is expected to approve third shot boosters of mRNA vaccines for everyone and the shots will be available 8 months from the date of your second dose (since I got my second shot in May, the third shot would not be until January). In the mean time I recognize that vaccines are not 100% effective and do not give me license to party like it’s 2019. I am grateful that I live in a country where vaccine supply is plentiful and all the adults in my family are well protected against severe disease, allowing grandparents to see their grandchildren. I have no problem wearing a mask inside public spaces for as long as it takes for COVID to become managed. Personally, unless there is irrefutable data that vaccine effectiveness has plummeted I would rather give my booster shot to someone at high risk in a developing country who hasn’t even gotten one dose. Beating COVID in America requires altruist behavior: people acting not just in immediate self-interest but making sacrifices for the larger community, including the vulnerable and children. How can we expect Americans to behave altruistically when the country itself is not acting altruistically towards other countries? When will we begin modeling the behavior we desperately need to promote? Moreover, helping other countries is not just altruistic; containing COVID in other countries will reduce the likelihood of new variants emerging overseas. The more viruses circulating, the more opportunity for new mutants to arise. Not only are SARS-CoV-2 viruses capable of evolving by mutation, but they can swap entire stretches of genetic material with each other through recombination (a version of viral “mating”).

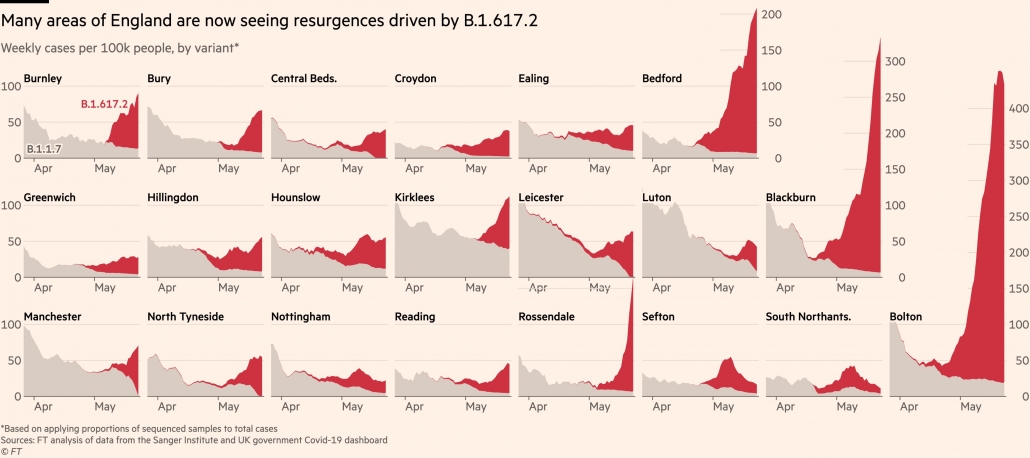

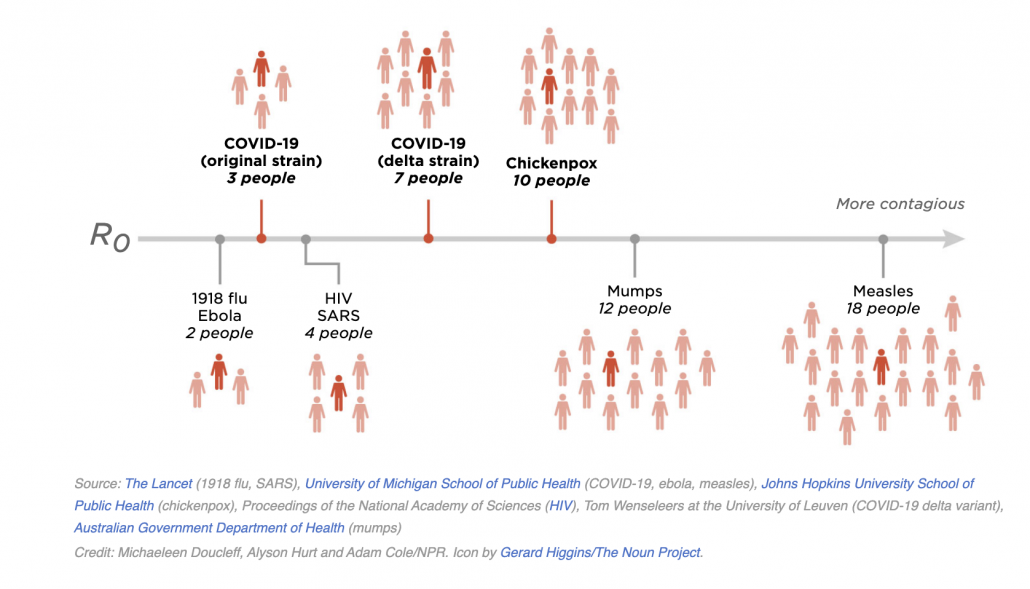

You heard: Delta variants are as contagious as chickenpox.

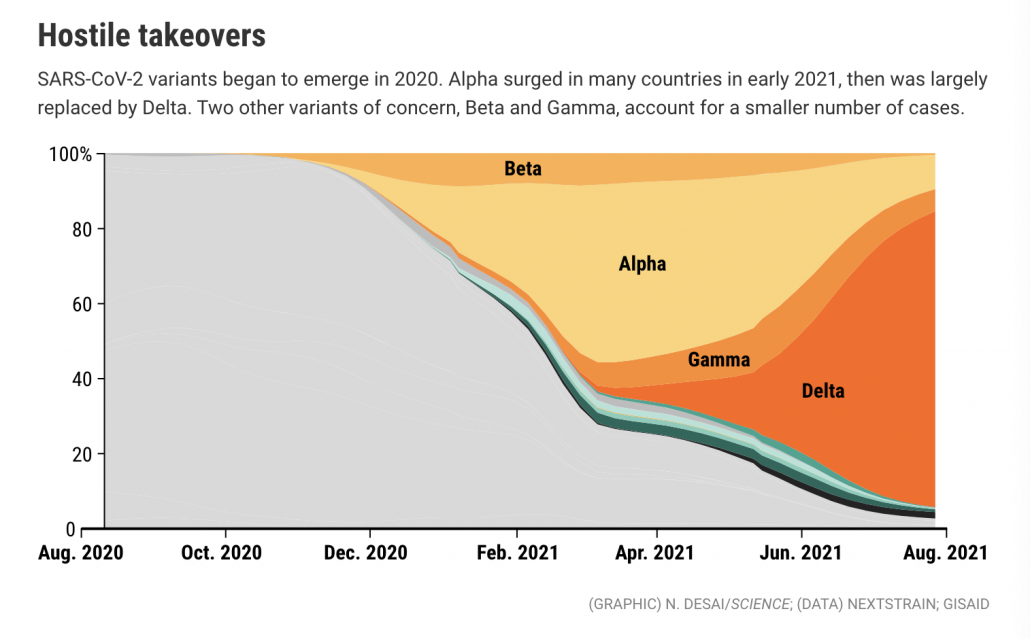

What that means: The Delta variant is estimated to have a higher R (reproductive number) than prior COVID strains, which means each infected persons pass on the virus to more people. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has been evolving rapidly since it emerged in humans into progressively fitter and more contagious forms. Prior to Delta, Alpha was considered the most transmissible variant, but has now been displaced by Delta.

Keep in mind that R is an average. Since SARS-CoV-2 is a good superspreader there will be a lot of variation in transmission. Many infected people will pass the virus on to no one. A small number will infect dozens. That’s why large gatherings are so problematic. If the infected person was capped out at passing the virus to only 7 people there would not be such a problem. But when a person who happens to be a superspreader (some people just shed a lot of virus) finds themselves in a densely packed gathering, the virus can rip through and infect numbers much, much larger than 7.

Being an average, R can also vary geographically based on local contact patterns. R in rural farm country where no mass gatherings occur will be a lot lower than in urban neighborhoods or tourist destinations that get densely packed. It is an open question the extent to which the elevated estimations of R for Delta reflect intrinsic properties of the virus versus sudden changes in human contact patterns in July and August when Americans loosened social distancing and stopped wearing masks.

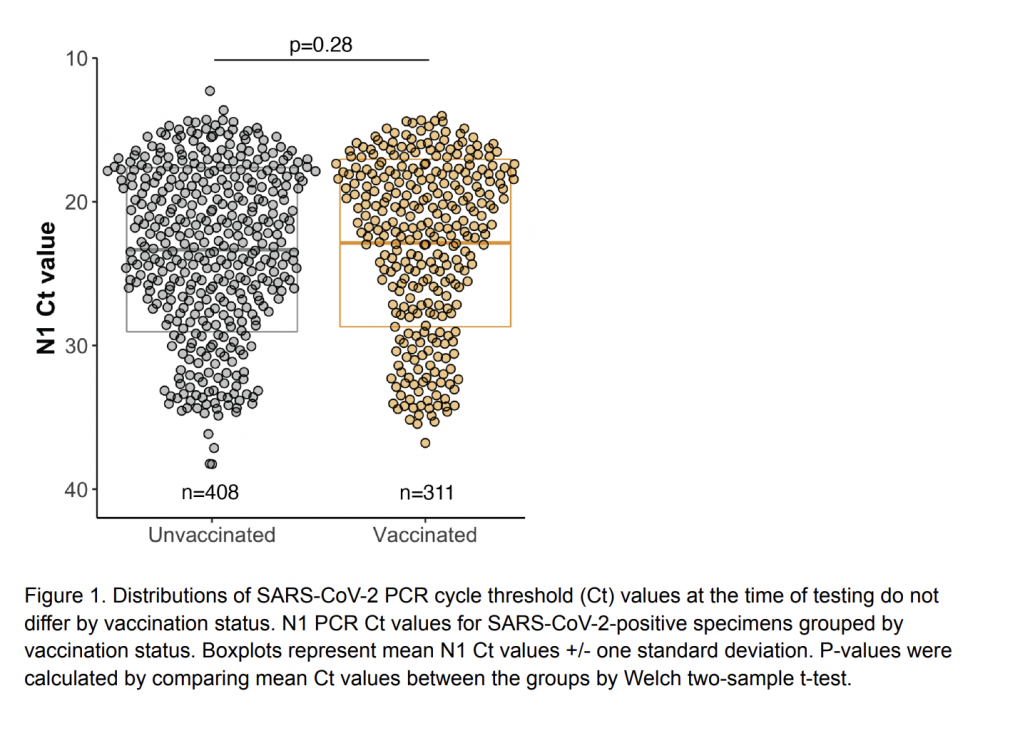

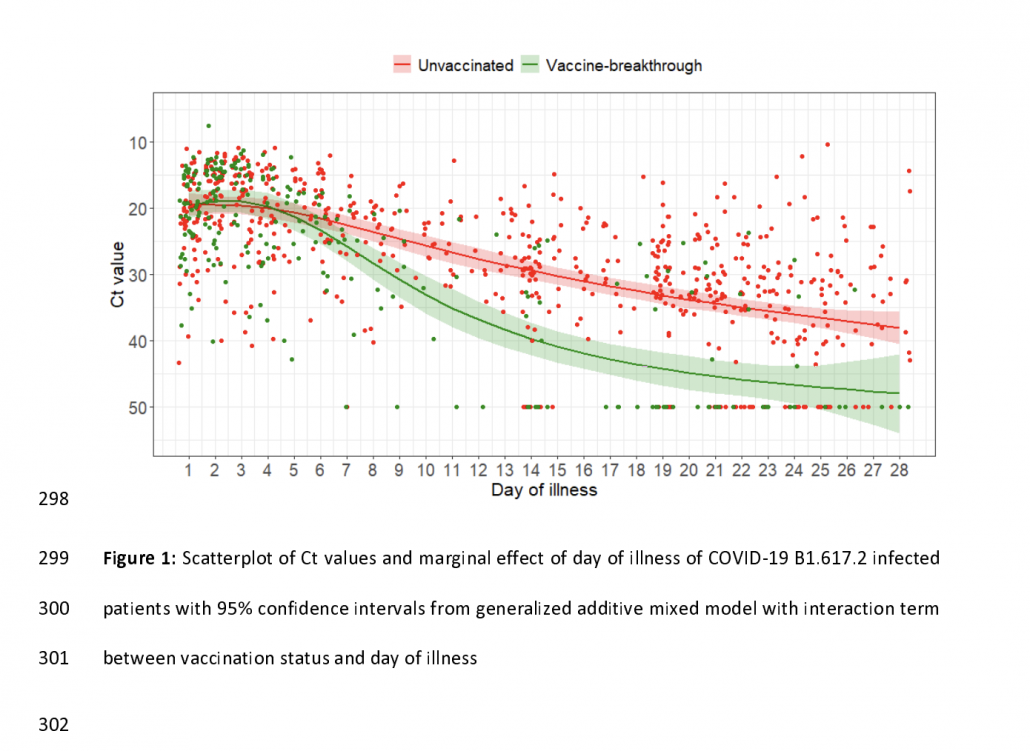

You heard: Viral loads are similar in vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

What that means: Viral loads represent the amount of replicating virus. Higher viral loads can lead to more symptomatic disease and/or higher likelihood of transmitting the virus to another person.

There is data showing similar viral loads in vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

But you get a more complete picture when you look at the time course of viral load. There are similar loads early in the infection when transmission occurs. But eventually an immune system primed by a vaccine is able to bring down the viral load much faster than a naive immune response, reducing the risk of severe disease and curtailing the period of infectiousness to other people. There is still a lot we need to learn about Delta, vaccines, and transmission, but in the mean time vaccinated people should recognize that the vaccine is good at protecting you but does not necessarily remove the risk of infecting others. That is why it is particularly important for vaccinated people to continue distancing when possible and wearing masks in dense or poorly ventilated spaces.

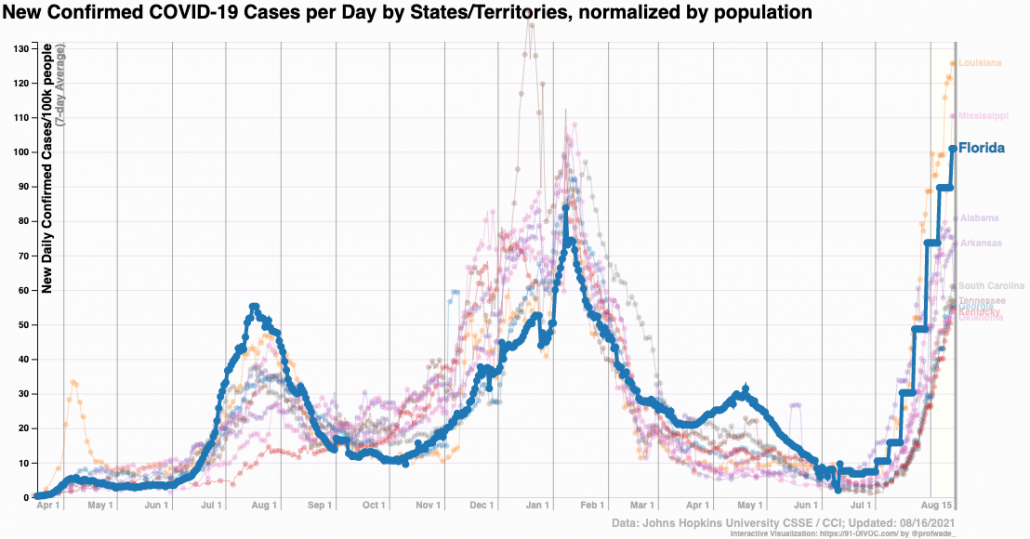

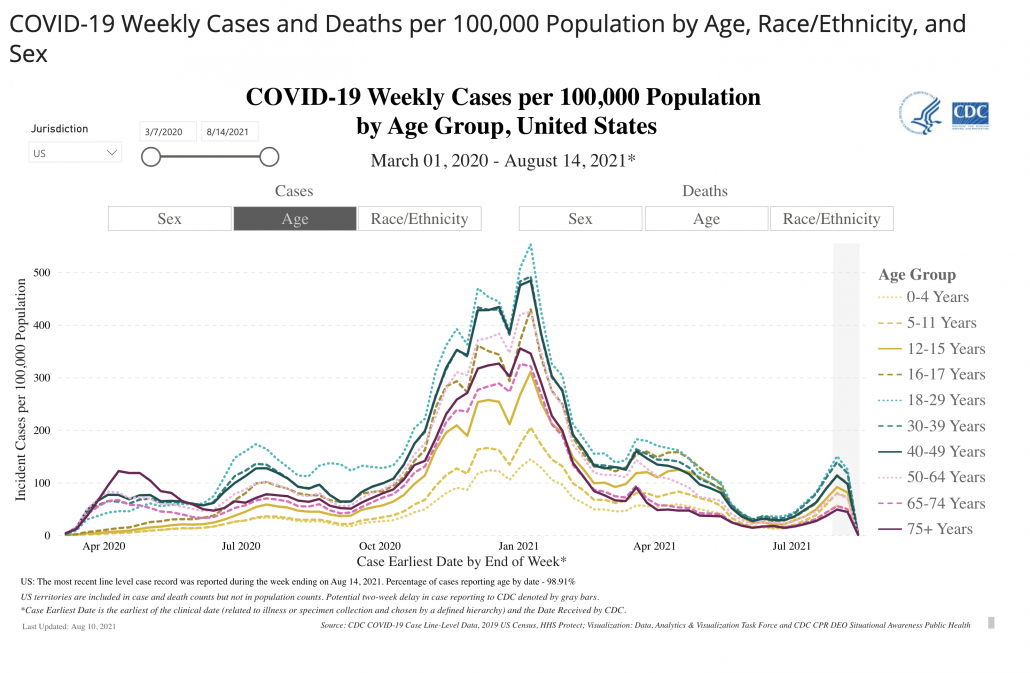

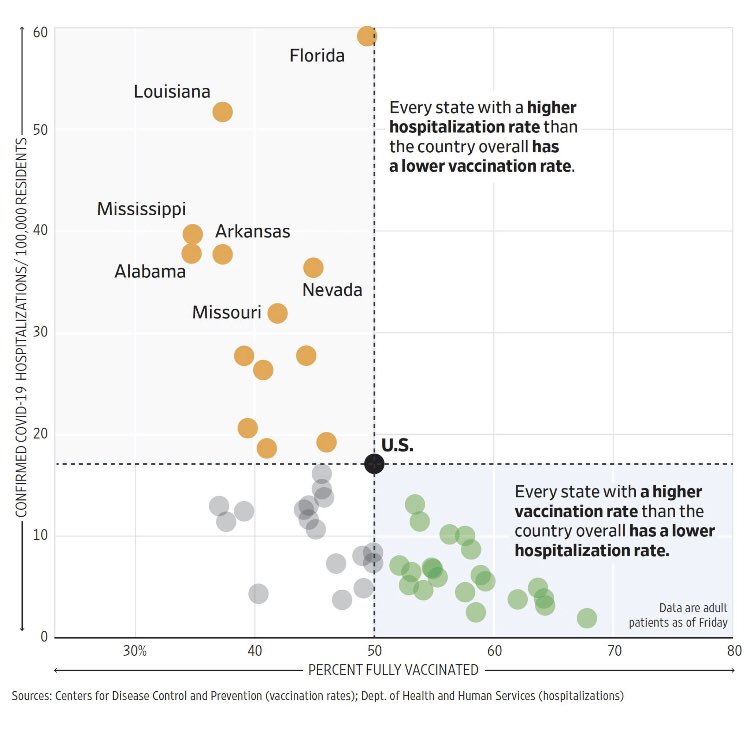

You heard: The Delta wave is primarily a problem in the South.

What that means: The Delta wave has spread everywhere. This summer’s epicenter in Southern states mirrors what happened last summer when COVID defied the expectation of being a winter disease that would fade as temperatures warmed, instead during in hot states where people crowd into air-conditioned buildings and spend less time outdoors during summer months. Lower vaccination rates and less social distancing in the South exacerbates the problem, but we saw this same pattern last year when vaccine was not a factor. Wildfire and smoke that keep people indoors in Western states could also drive up transmission in those areas.

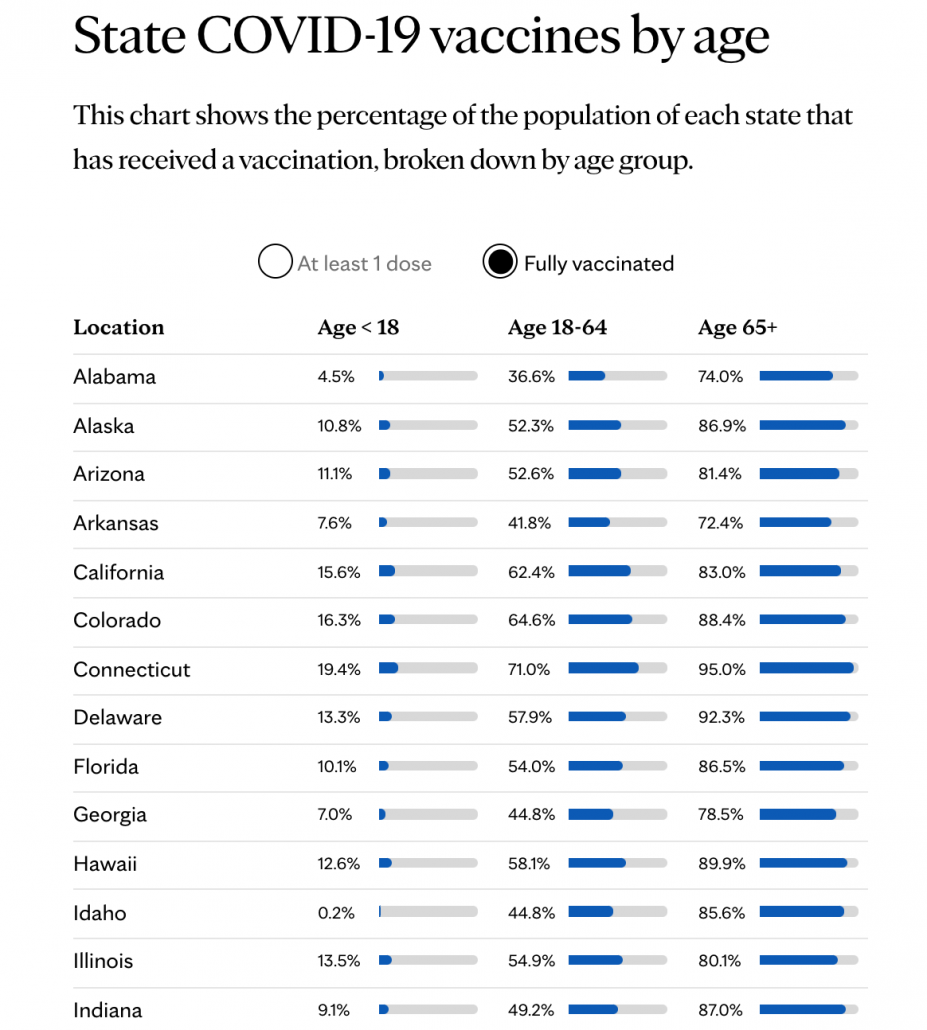

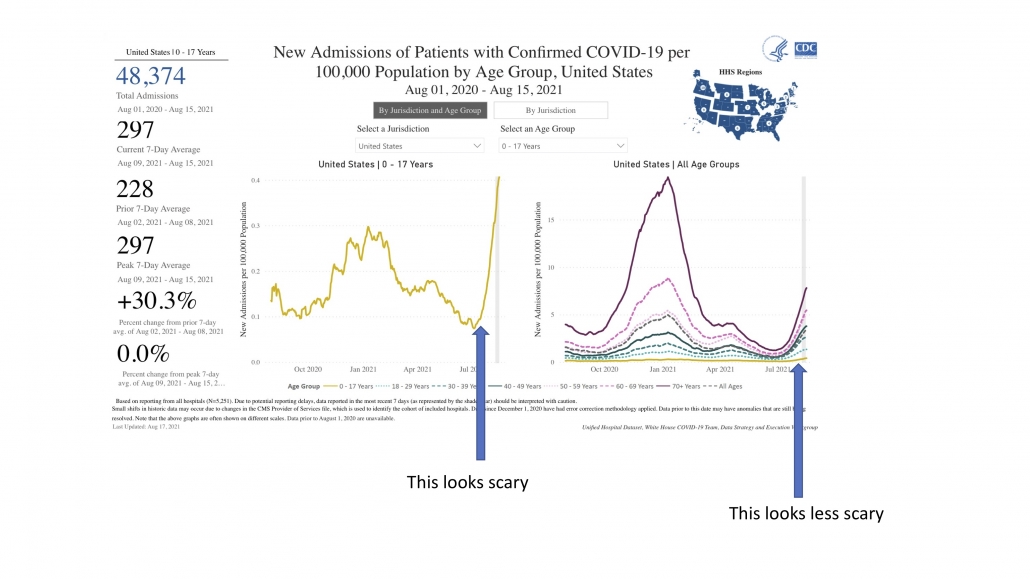

The surge appears driven by younger people who tend to have lower and more variable vaccination rates across US states.

You heard: The current wave is not a big deal because old people are protected so it’s just mild infections.

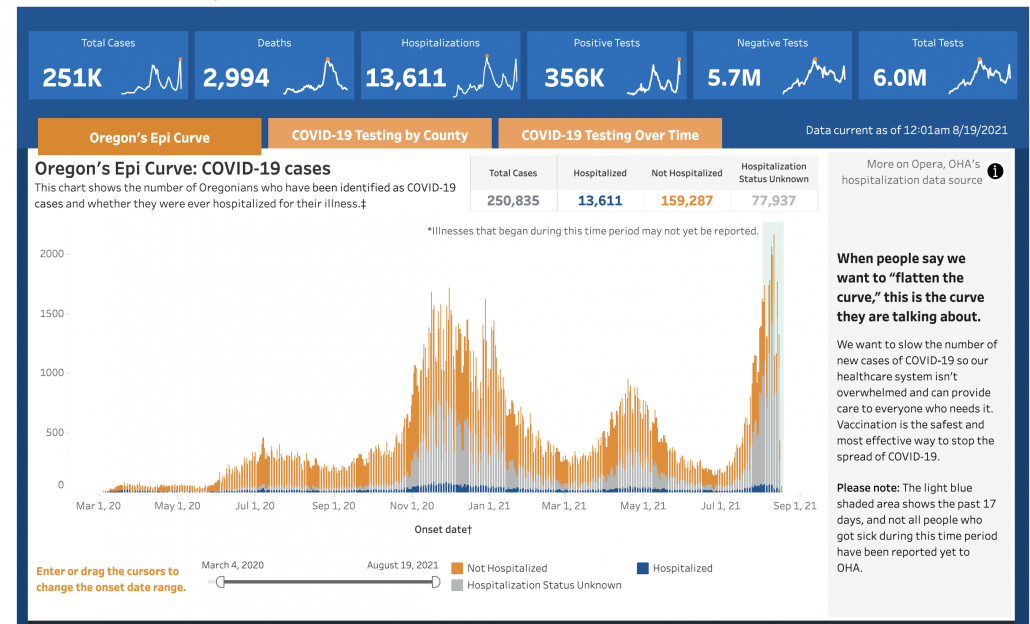

What that means: Louisiana, Florida and Oregon have reported record hospitalizations in recent weeks as the Delta variant spreads. Recall that hospitalization and death are lagging indicators which means that we won’t observe the real toll of the current surge in cases for several weeks.

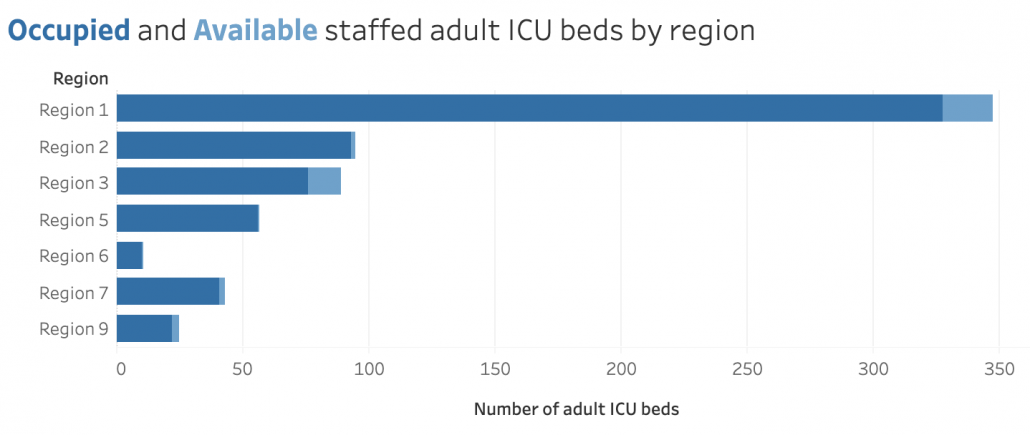

COVID becomes even more lethal when heart attack and car accident victims can’t get a hospital bed. Even pediatric wards are filling up. I challenge anyone who doesn’t think COVID is a big deal right now to volunteer one hour’s time in an over-crowded ICU. Our doctors, nurses, and staff were already seriously burned out going into the summer. August is supposed to be the quiet before the storm when flu season hits in the fall. Exhausted medical staff are more likely to make mistakes. Overtaxing our medical systems has serious knock-on effects.

You heard: Mild cases are okay. In fact, mild infections in vaccinated people could serve as a natural booster.

What that means: There is a tendency in the press to downplay “mild” COVID cases. Yes, a week or two fevering in bed is something we can all tough out. But we all know healthy people who have had seemingly mild cases turn into long-running complications, either cardiovascular, neurological, or pulmonary. Mild breakthrough infections also appear to be able to cause “long COVID” but of course we need better longitudinal data for Delta. Our health tracking systems are not well designed to study long-term COVID complications so methodologically there is a lot we still don’t know.

You heard: Delta is sending more kids to the hospital.

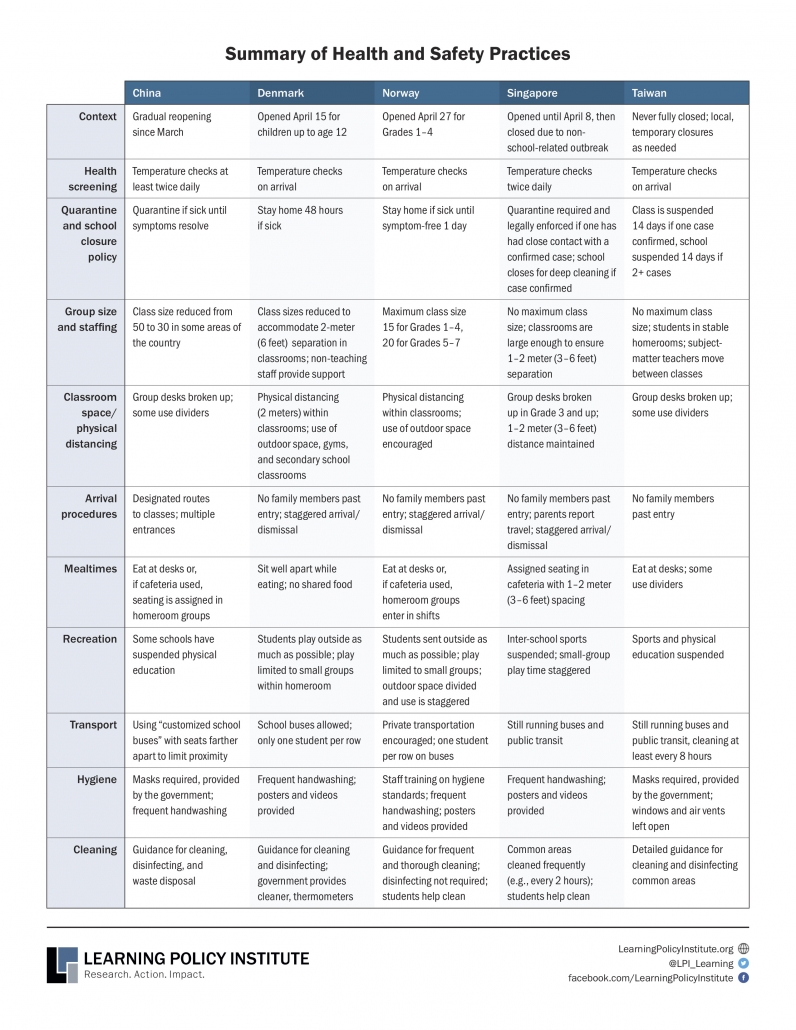

What that means: The rate of hospitalization of kids with COVID is increasing, but the overall risk is still low. But kids are more susceptible to a range of respiratory viruses, including RSV and flu. RSV and flu were both suppressed by school closures last year and there is a risk when school starts of kicking off outbreaks of other respiratory infections in kids whose immune systems have been dormant for a year. A big concern that pediatric wards filled with kids with other respiratory infections might not have capacity for the additional kids that enter with COVID. Even more reason for schools not to be complacent prepared this year. A lot of schools are drawing on last year’s experience to assume that transmission will be low in kids. But Delta is more transmissible and strategies that worked last year may be less effective this year. We owe it to our kids to bring our A game this fall. That means routine testing in schools (pooled if necessary), intensive contact tracing, tents for outdoor lunches, extra teachers for smaller class sizes, mandatory vaccination of teachers and staff, extra staff for facilitating online learning for kids that have to be temporarily isolated at home (any kid with a sniffle could miss school until they get a negative COVID test — just wait until cold season hits).

Why is it taking so long for vaccine to become available for kids <12? The clinical trials for young kids are much smaller, enrolling one-tenth the number as were in the adult trials, which means they require a longer period of data-gathering to achieve sufficient power. Contrary to widespread perception that COVID trials in adults were “rushed”, the trials simply benefited from “blank check” cash influxes that allowed enormous numbers of volunteers to be enrolled to power the study. Not having to wait around for people to get infected also sped up the trials (the *one* benefit of letting COVID rip through the globe).

You heard: COVID vaccines cause sterility.

What that means: You get your news from the wrong sources.

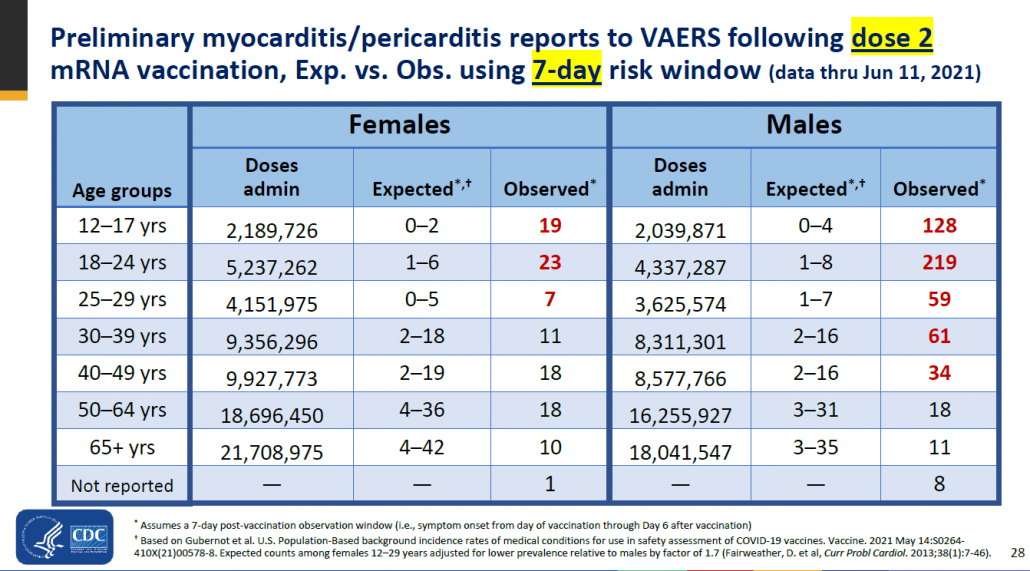

Here’s an example of a rare side effect of the COVID vaccine in children that legitimately occurs and has received attention. An outsized number of vaccinated people (particularly boys ages 18-24) experienced myocarditis (inflammation of the heart). However, the rate of myocarditis is still very rare even in the highest risk category (219 out of >4 million) and the condition generally recedes after a few months. Media headlines about heart inflammation in kids naturally cause anxiety in parents, but this is an exceedingly small risk compared to getting naturally infected with COVID.

You heard: CDC recently changed its guidance on mask wearing for vaccinated people.

What that means: Effectively, that Americans now have no idea when they are supposed to wear masks.

What prompted the change? The CDC changed the mask guidance for vaccinated people after seeing the data from an outbreak in Provincetown, Massachusetts during Fourth of July festivities. The vast majority (74%) of the 469 COVID-19 cases from the Provincetown outbreak were in fully vaccinated people. Most of this population was adult males (average age 40). Almost all the viruses were Delta (90%). Overall, 274 (79%) vaccinated patients with breakthrough infection were symptomatic (although asymptomatic cases were likely missed). Measures of viral load in vaccinated people who got infected were similar to those who were unvaccinated (viral load is often used as a proxy for contagiousness). Five COVID-19 patients were hospitalized, four who were fully vaccinated; no deaths were reported. The data was difficult to interpret because it was not age-stratified.

What are the changes for fully vaccinated people?

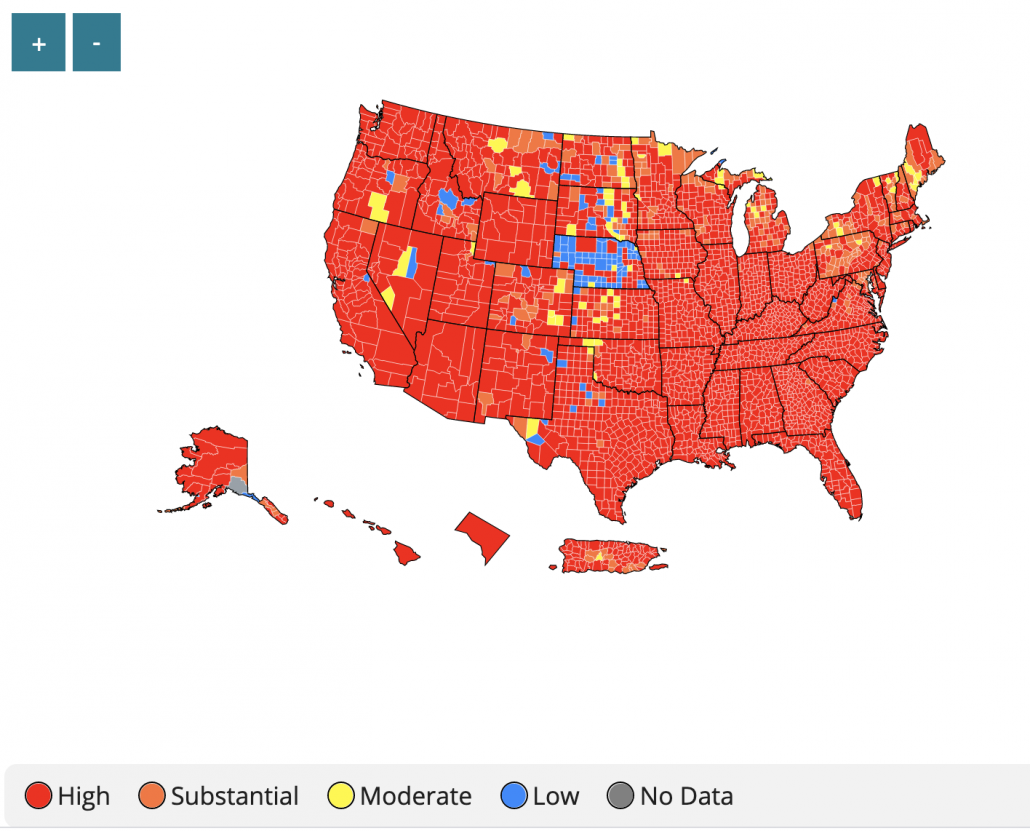

CDC addition: Wear a mask in public indoor settings in areas of “substantial or high transmission”.

My translation: At first I thought this meant “settings with high transmission” like bars, restaurants, buses, but if you click the link it means US counties with high COVID activity. Which includes almost all counties, even in Vermont. So really this is just: “Wear a mask in all public indoor settings“. What does “public” encompass? My interpretation includes any place you encounter strangers, including private businesses.

CDC addition: Wear a mask regardless of the level of transmission, particularly if they are immunocompromised or at increased risk for severe disease from COVID-19, or if they have someone in their household who is immunocompromised, at increased risk of severe disease or not fully vaccinated.

My translation: You should already be doing this (see above)

CDC addition: Fully vaccinated people who have come into close contact with someone with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 to be tested 3-5 days after exposure, and to wear a mask in public indoor settings for 14 days or until they receive a negative test result.

My translation: You should already be doing this (see above).

CDC addition: CDC recommends universal indoor masking for all teachers, staff, students, and visitors to schools, regardless of vaccination status.

My translation: You should already be doing this (see above).