Will America Take the COVID Vaccine?

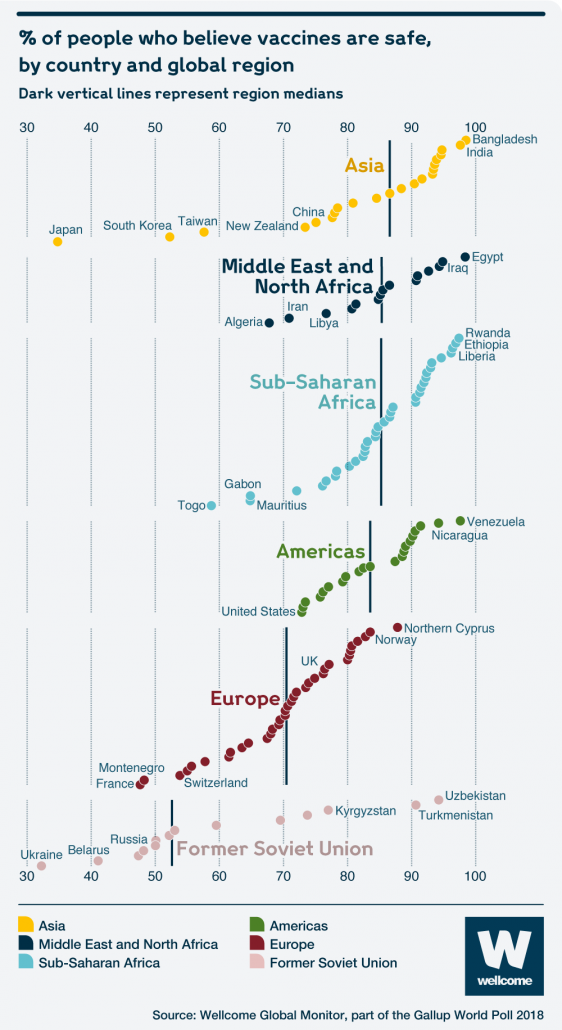

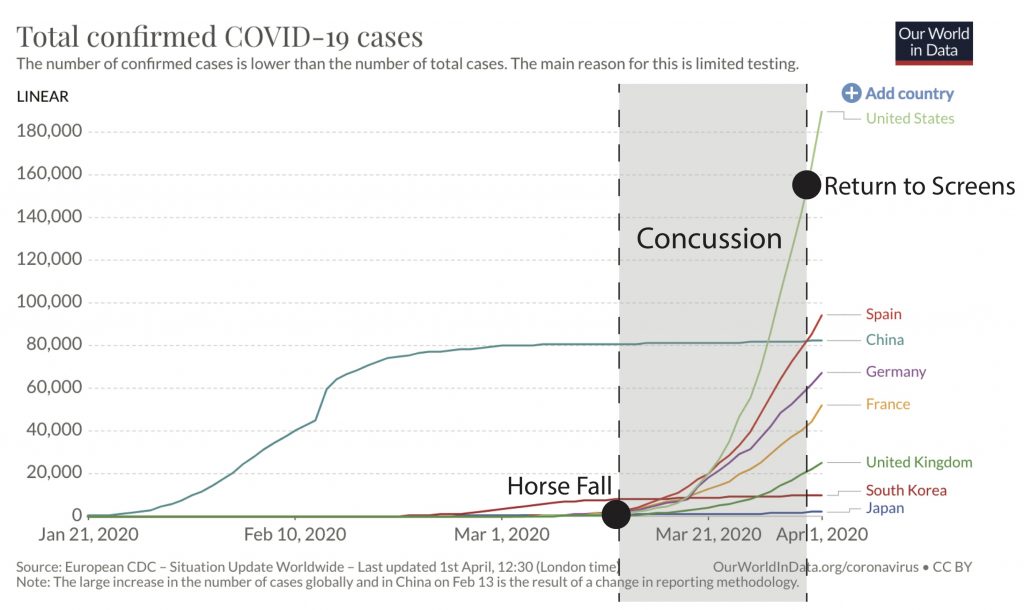

As scientists race to develop a COVID vaccine at record pace, it’s worth noting that half the country isn’t planning to take it. Or at least isn’t sure if they’ll take it. Millions of Americans opting out of a COVID vaccine would be catastrophic for public health and economic recovery. So it’s worth understanding why so many Americans may be inclined to take a pass.

The vast majority of Americans vaccinate their kids without thinking twice. By 35 months, over 90% of US kids have received their routine vaccinations for polio, measles-mumps-rubella, hepatitis B, and chickenpox.

But there is a vocal and politically active minority that questions vaccine safety and fights for the right to opt out of school immunization schedules based on personal beliefs. It is critical to recognize that their argument is generally not a scientific one, but instead framed as ‘pro-choice’. The freedom for them to decide, not the government, what goes into their bodies and their children’s bodies. Can’t those risk calculations be left to the discretion of a family and their pediatrician?

This was settled legally in 1905. Reverend Henning Jacobson refused to comply with the Massachusetts Board of Health’s regulations requiring smallpox immunization. The famous Jacobson v. Massachusetts Supreme Court ruling upheld the immunization requirement as a reasonable exercise of state police power and remains settled law.

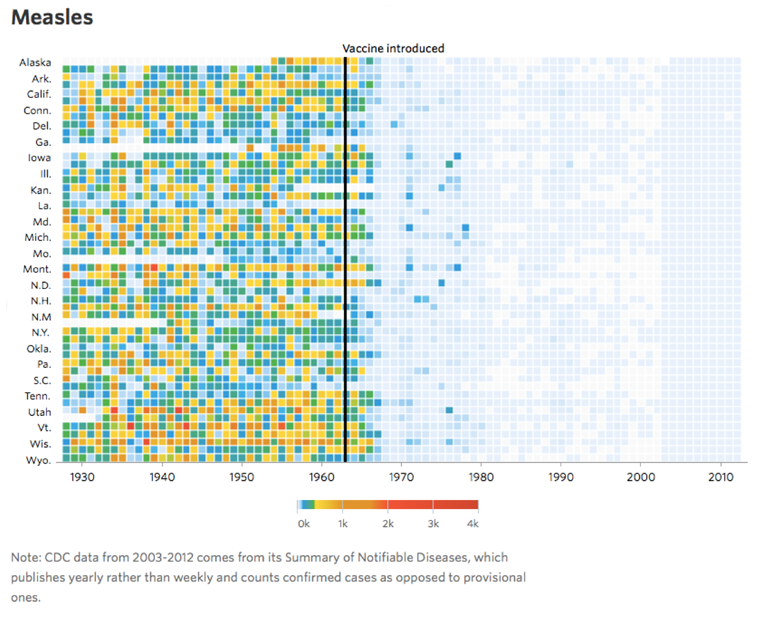

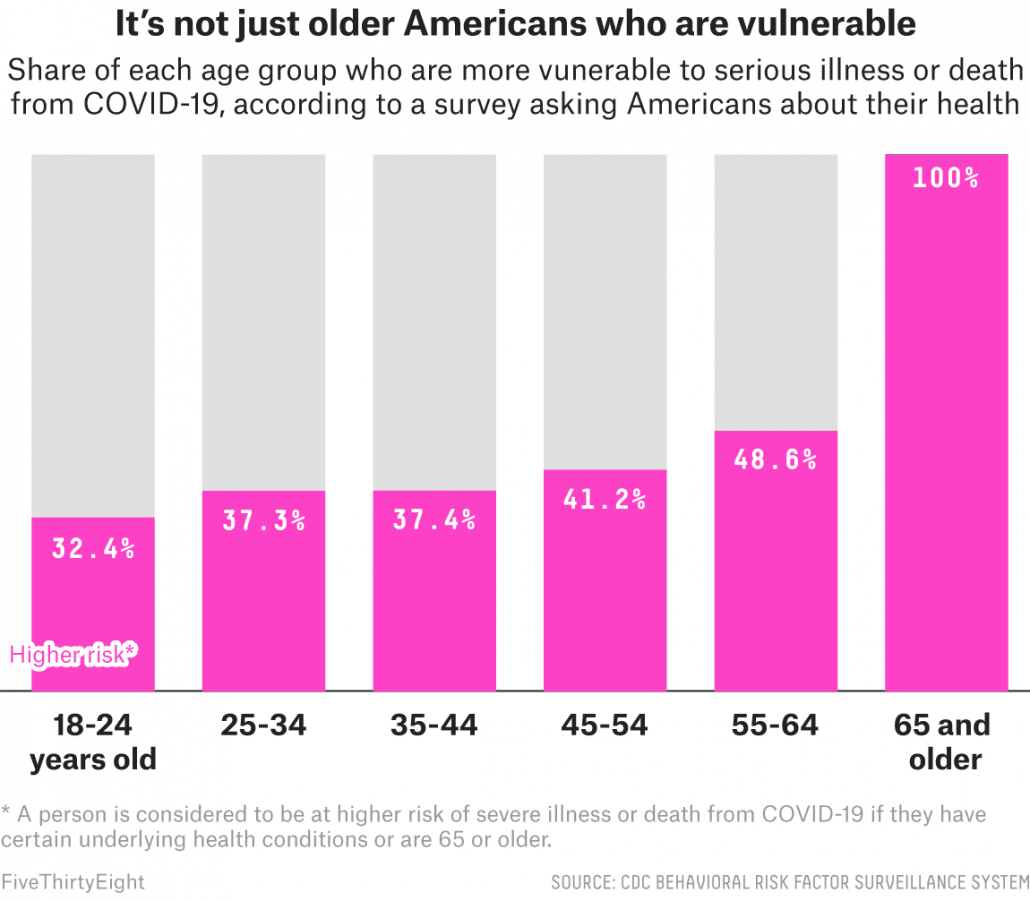

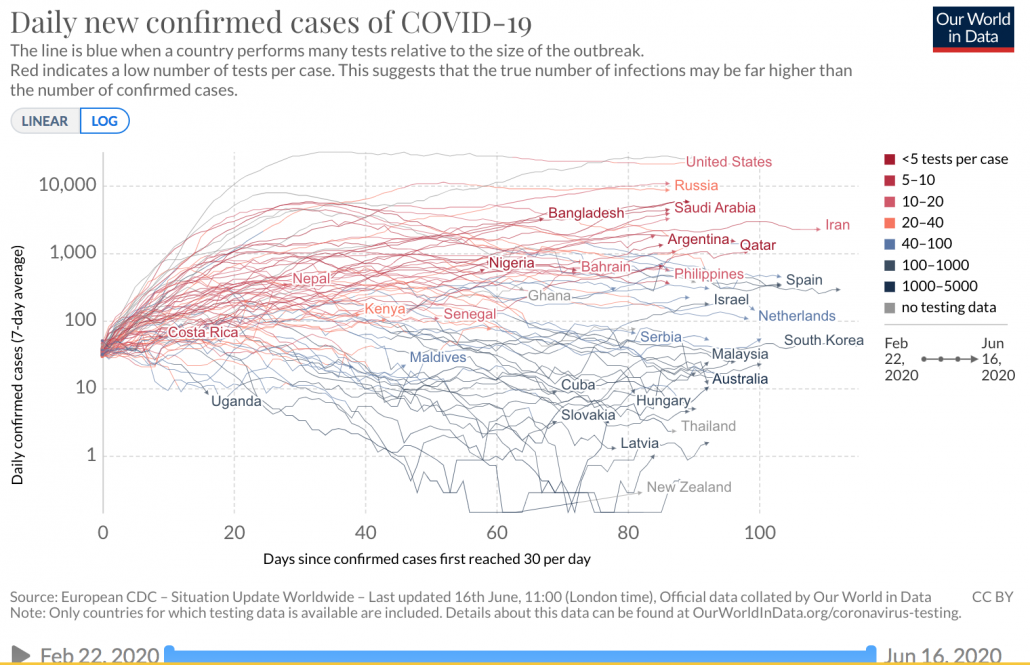

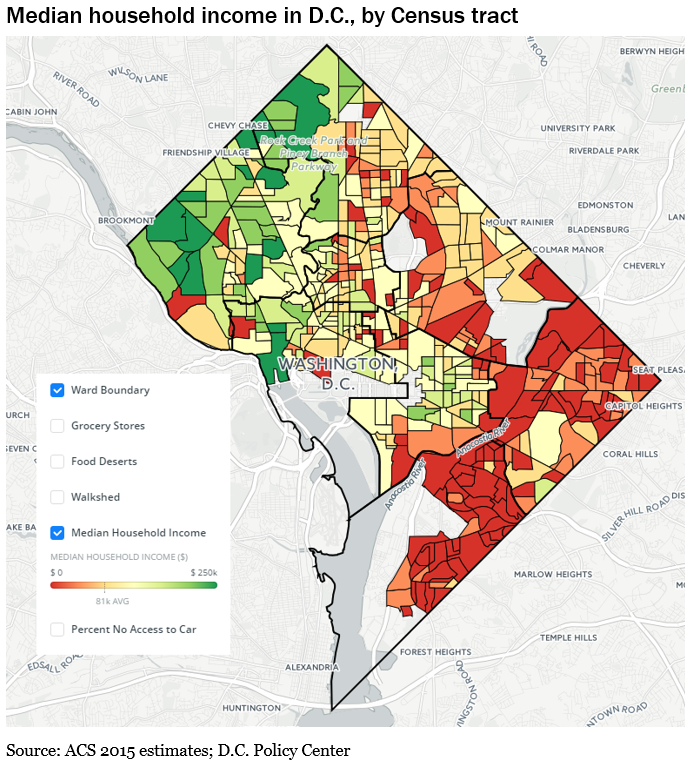

There is a fundamental flaw in the argument that the decision to vaccinate or not is a personal decision that should be left to an individual’s beliefs. America is a country that prizes individual freedom, but there is a reason the Jacobson v. Massachusetts ruling upheld the immunization requirement. It’s not just that Americans have difficulty making abstract risk calculations around bugs they can’t see. It’s two big words: herd immunity. Herd immunity means that you don’t need every person to be vaccinated against a disease to protect the entire community. For measles, it means you can prevent the virus from transmitting in a community even if only ~90% of kids are vaccinated. This is very important since babies that can’t be vaccinated until they’re 12 months old. But we can still protect them by vaccinating older kids. It’s one thing for an individual to make a risk calculation that affects just their own health. But the government can step in when it threatens the lives of the 3+ million babies born in the US each year. (But for some reason the we’re all in this together message doesn’t resonate as well with Americans as don’t tread on me. This is why America is leading the world in COVID deaths.)

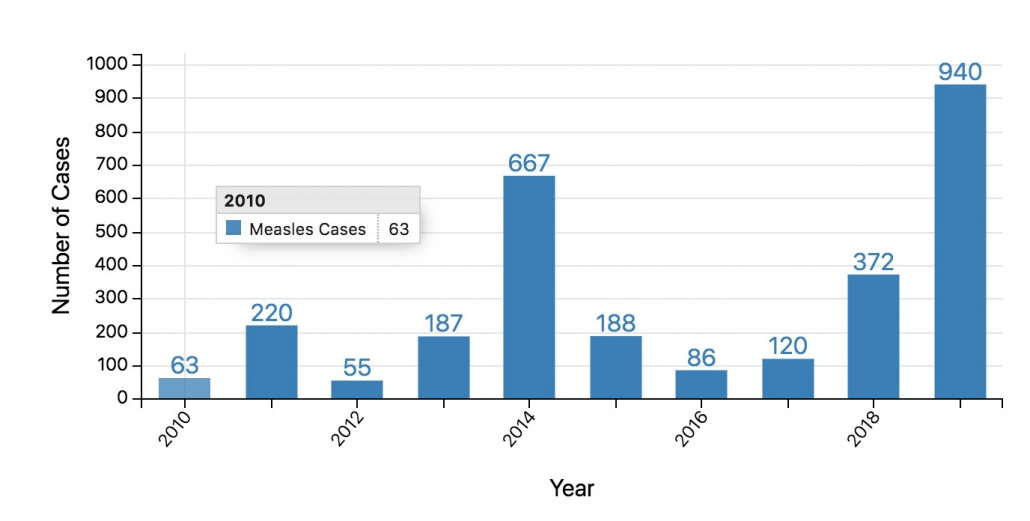

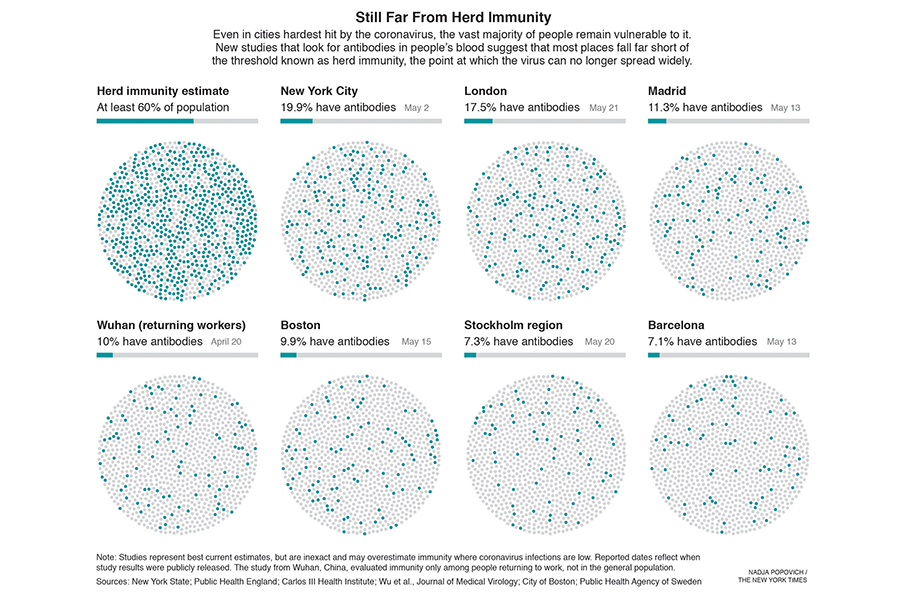

Sidebar on Herd Immunity. Herd immunity is a threshold, not a continuum. Once you slip beneath the threshold you have outbreaks. That’s why we’re having new measles outbreaks even though the vast majority of America’s kids are still vaccinated. For a virus like SARS-CoV-2 that is less transmissible the percentage of people you need to vaccinate to achieve herd immunity is fortunately lower (60% is estimated).

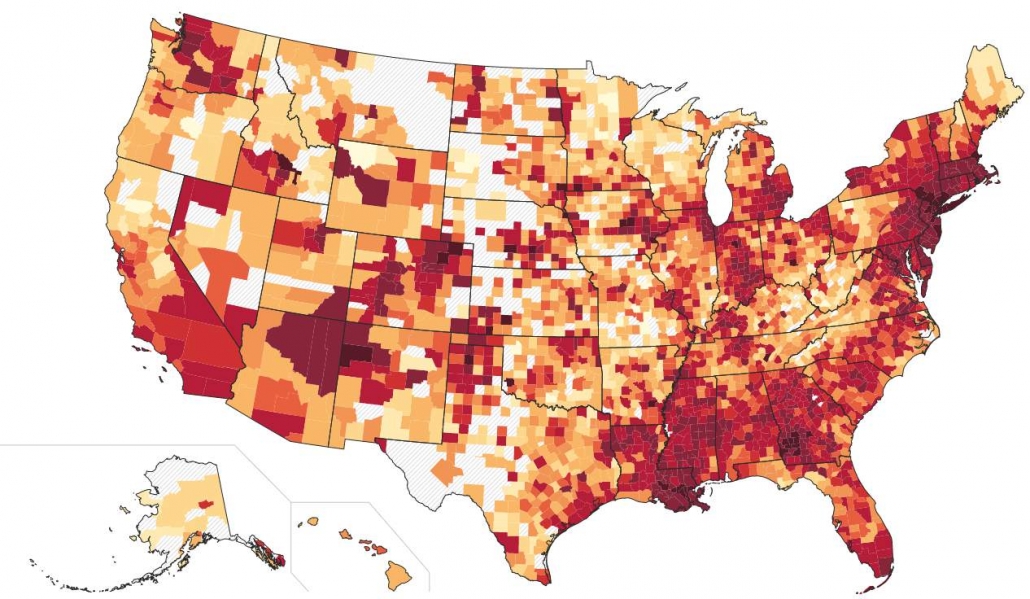

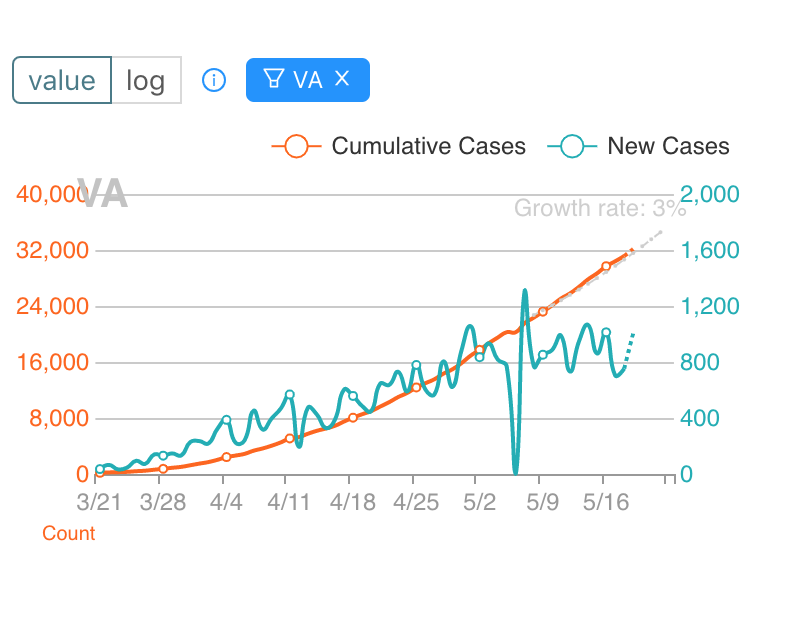

We still don’t know exactly how many people have been infected with COVID, although serology studies in different countries give a rough estimate. Even hard-hit cities like New York are still way below the 60% threshold. Sweden was an early advocate of the idea that letting the virus naturally infect the population would increase herd immunity and protect people during later waves. The epidemiologist who pushed this idea has since admitted that he badly miscalculated.

As long as we’re talking about herd immunity, I also need to mention that a lot of kids have been skipping pediatrician visits during COVID and missing routine vaccinations. Because a measles outbreak on top of a COVID pandemic is exactly what America needs right now.

States have always had medical provisions permitting individuals who are immunocompromised or have allergies to vaccine ingredients (such as eggs) to opt out of immunization requirements. Most states have also included exemptions for religious, philosophical, or personal beliefs. However, for most of the twentieth century use of personal belief exemptions remained limited to isolated communities such as the Amish. Some states, such as West Virginia, didn’t offer non-medical exemptions at all.

Conspiracy theories about vaccines have been around for a long time. But questions of vaccine safety went mainstream in 1998 when the British doctor Andrew Wakefield published a deeply flawed study linking autism and MMR vaccines in The Lancet. Poor quality studies get published and retracted all the time. They generally don’t lead to the erosion of decades of public health gains and deaths of children. But in this case it took a glacial 12 years for the Wakefield study to be officially retracted by the journal. Wakefield was deemed to be such a bad actor that his medical license was revoked and he was banned from medicine.

But the damage had been done. Personally, I have considered trying to estimate how many lives were lost to pathogens because of the wave of vaccine hesitancy Wakefield unleashed, not just in America but in other countries as well (Europe has seen vaccination rates wane and measles cases spike again). In a twist of fate, Wakefield’s discredited study did more to erode public confidence in vaccines than any of the verified complications that vaccines have actually caused over their long history.

Overall, the benefits of vaccines far outweigh the risks. But tragic complications do rarely occur:

List of complications associated with vaccines, compiled by CDC.

Dengue vaccine in the Philippines

RSV candidate failure

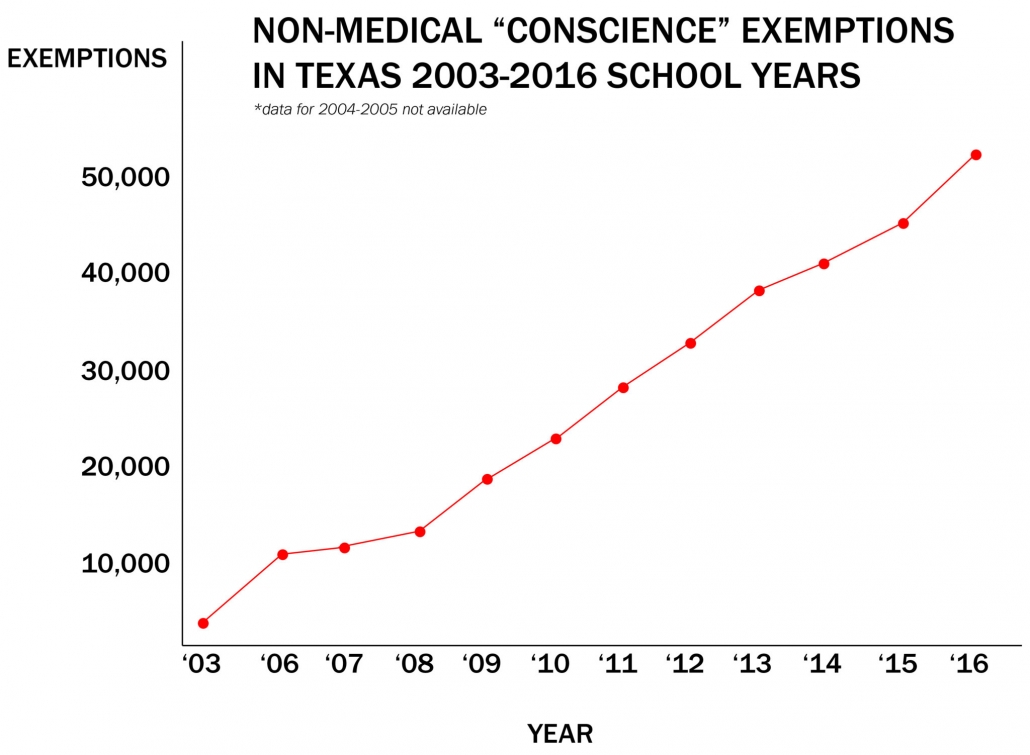

Why was Wakefield so successful in peddling misinformation? Because he preyed on vulnerable parents trying to find answers about their autistic kids. Wakefield, who now lives in Texas, continues his misinformation campaigns in vulnerable groups. His campaign to discredit the MMR vaccine among Somali immigrants in Minnesota led to state’s worst measles outbreak in decades. Wakefield also got a leg up from celebrities, including instant public health authority Jenny McCarthy. The combination was potent. Non-medical exemptions from school immunization requirements quadrupled between 2003 and 2016.

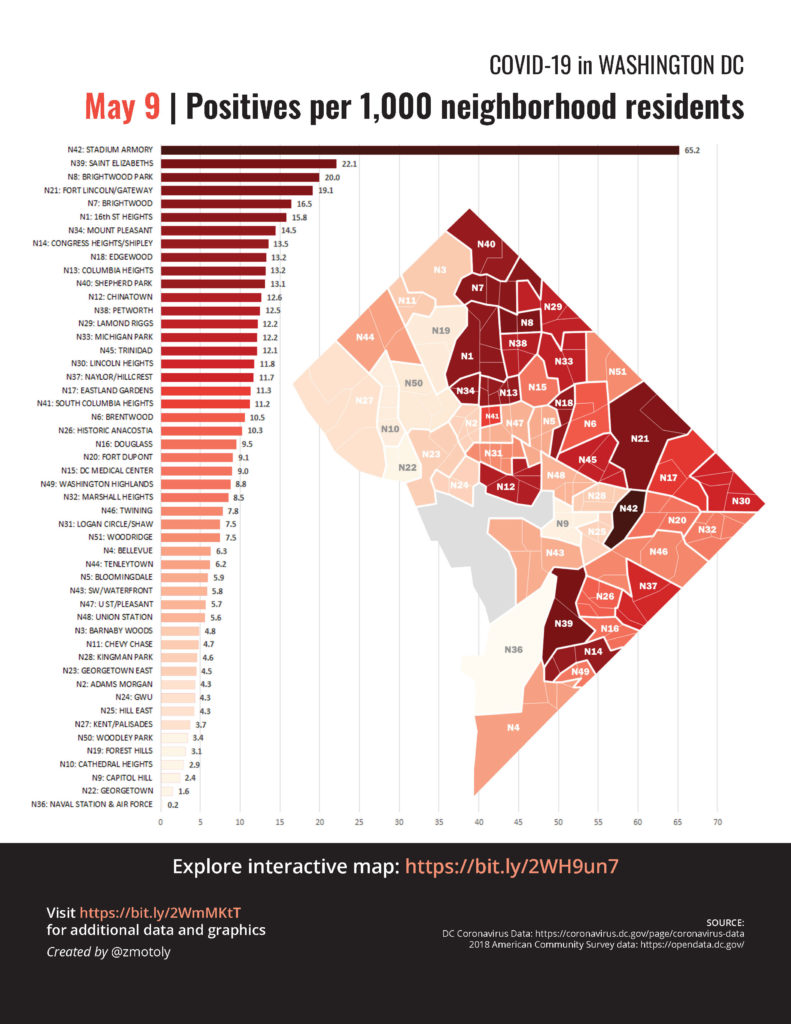

Although the proportion of kids getting exemptions from vaccines actually remained relatively low at a state level, exempted kids tend to be geographically clustered, creating pockets of susceptible hosts that viruses like measles can easily exploit.

Vaccine hesitancy spreads the same way as a riot. Very few people would throw the first rock through a store window. You need the outlier/psycho for rock #1. But one or two might be willing to join in after rock #1. And a larger number after rock #s 2-10. And so on. Similarly, at first only an extremist in a community requests a vaccine exemption based on personal beliefs. But word spreads. There might be coverage in the local newspaper (anything that threatens kids is red meat for journalism). Suddenly people in the community are primed to see any evidence that vaccines might cause problems. We all know that young children get fevers and strange illnesses all the time. Most pass without complication. But by chance some of those illnesses are going to happen shortly after a kid gets vaccinated, now causing alarm. It’s easy to see how vaccine hesitancy can quickly snowball in a community.

Until the measles and mumps outbreaks return. In the fight against vaccine hesitancy scientists and doctors stood no chance against moms with fervent beliefs. But a new powerful ally emerged: moms who didn’t like their babies getting measles. The Great California Mom Wars* finally concluded with new legislation in 2015 that rolled back personal belief exemptions. Other states with bad measles and mumps outbreaks like Washington followed suit.

* While I like the idea of Mom Wars, Team No Measles was also helped by the big measles outbreak at Disneyland. It helps to have a powerful corporate backer who doesn’t want the Pirates of the Caribbean to actually include 16th century diseases.

Given that poor quality studies get published and retracted all the time, and complications with vaccines have occurred repeatedly in history, it’s worth exploring why Andrew Wakefield’s anti-vaccine message resonated so strongly with Americans at that particular moment in time.

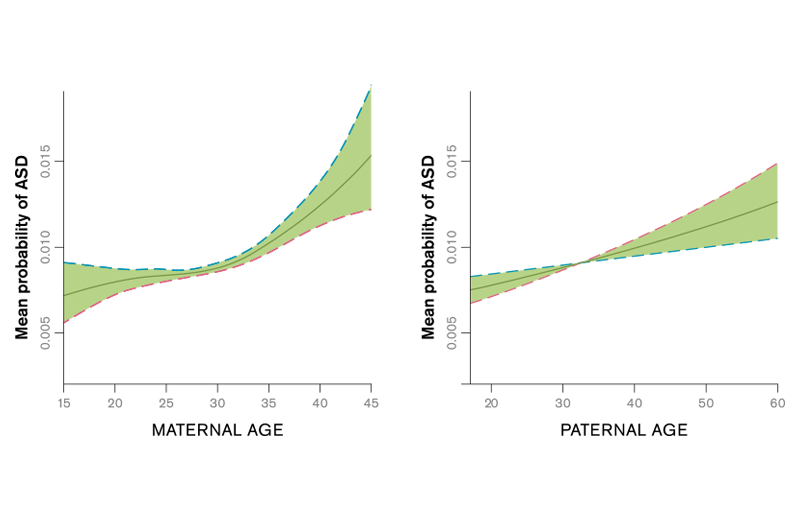

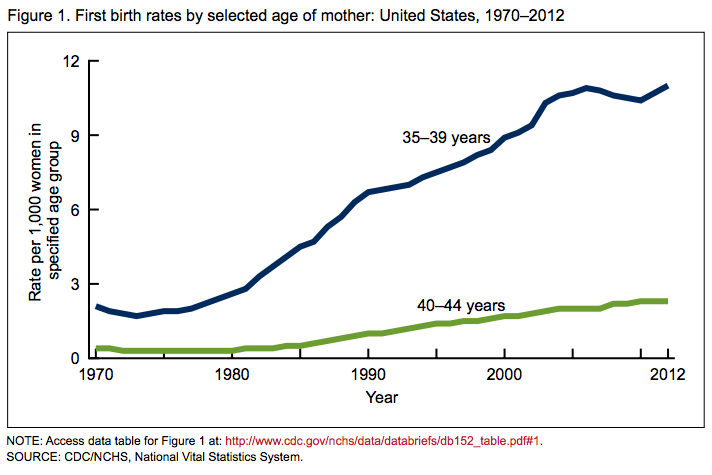

- Autism was on the rise. Parents sure don’t like kids getting diseases with no explanation.

By the way, if MMR vaccine wasn’t causing autism’s rise, what was?

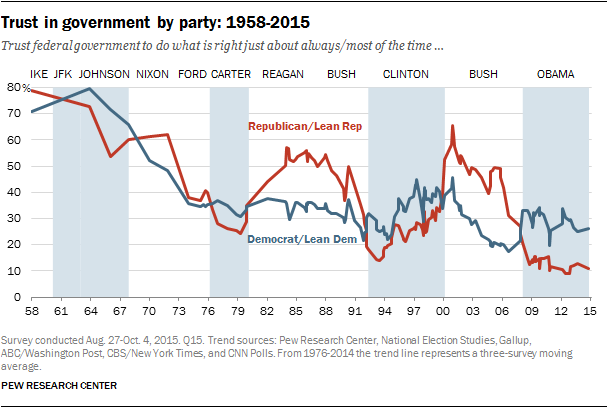

2. American trust in government has been eroding. Americans who opt out of vaccines are scattered geographically and politically. But they tend to have one thing in common: a deep distrust of the influence of pharmaceutical companies and government in the practice of medicine in America.

3. Distrust of Big Pharma. I can’t blame anyone for distrusting the US medical establishment while the country is in the midst of an opioid crisis that was entirely manufactured by a duplicitous drugmaker and rings of complicit doctors who profited. All of whom should be prosecuted for their crimes.

That said, vaccines have saved more children’s lives than anything except clean water. Epidemiologists who study infectious disease patterns know that vaccines are the most cost-effective way to save children and improve public health. The millions of children Bill Gates’s foundation has saved through vaccination programs in the developing world should earn him a Nobel Peace Prize. You won’t find a legitimate epidemiologist who doesn’t rank vaccines as one of humanity’s greatest inventions, second maybe only to fire.

When aliens finally visit Earth, the one technology they’ll take back with them is the one that magically nudges our immune systems into mounting just enough response against bits of bad bugs so that we’re fully defended against future attack, but not so much that we get sick. Now that will be worth traveling lightyears for.

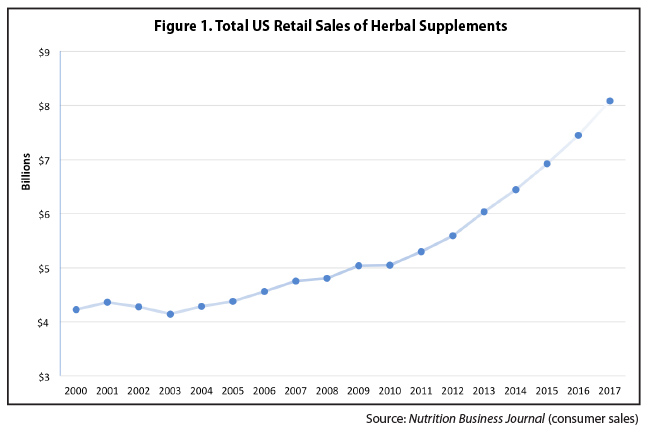

That said, I understand the appeal of homeopathic medicine. Western medicine is failing us in many domains, including pain relief, mental health, and diseases that have complex sequelae like Lyme. I also understand the desire to reclaim autonomy over personal health decisions. I opted for an unmedicated birth via midwife because I wanted to be in control.

But I would like to point out that homeopathic medicine is also a rapidly growing $8 billion industry. One that financially benefits from the corrosion of public trust in vaccines and Western medicine. And for which the efficacy of products is largely untested. It should then come as no surprise then that anti-vaccine platforms have received substantial funding from sellers of natural health products.

Sidebar on Human Microbiome. Remember back in the 80s when life was simple? Germs were bad. Anything that killed them (e.g., antibiotics) were good. Why did everything have to get so complicated in the 21st century? Two words: peanut allergies. The rise of peanut allergies was first detected in 1995. Asthma had also been increasing in kids. Researchers began to question whether exposure to certain germs was actually good for immune development. But figuring out which bugs are beneficial is not straightforward. In fact, it’s at least a $153 million question, spearheaded by the Human Microbiome Project. It will take decades of research to figure out the precise functions of the trillions of bacteria that colonize the human body, spanning 500 to 1,000 different species. In fact, the human body contains as many bacterial cells as human cells.

“Humans are ecosystems, where the microbes that live on and within us (the human microbiome) constitute an organ at least as essential to health as our liver or kidneys. The immune system is a learning device, and at birth it resembles a computer with hardware and software but few data. Additional data must be supplied during the first years of life, through contact with microorganisms from other humans and the natural environment. If these inputs are inadequate or inappropriate, the regulatory mechanisms of the immune system can fail. As a result, the system attacks not only harmful organisms which cause infections but also innocuous targets such as pollen, house dust and food allergens resulting in allergic diseases.” –Bloomfield et al., 2016

Awareness of the vital functions of our natural microflora has changed how we practice medicine and public health. Antibiotics are now used more judiciously in humans and livestock. But there is a new risk that we have simply replaced one oversimplified dogma (germs are bad) with a new one: germs are good. It’s one thing to let your kid get exposed to different microbiota by playing in the mud or getting licked in the face by a dog. But it’s another to try to build immunity by letting your kid get naturally infected with measles or mumps. In fact, this would have the opposite effect, since a measles infection can cause a form of ‘immune amnesia’ and impair the body’s future immune defenses against a range of other bad bugs.

Another way we simplify the complex role of microorganisms in human health is by guzzling probiotics. Probiotics, which contain various assortments of live beneficial bacteria and/or yeast, are projected to be a $60 global industry by 2024. Probiotics are potentially helpful when taken with antibiotics to offset the drug’s disruption to microflora. But as a regular dietary supplement, their health claims are not verified by the FDA and tend to outpace the science. No probiotic has been approved by the FDA to treat, cure or prevent a specific disease.

I’ll be the first to admit the human immunity is blood complicated. Here’s a cheat sheet to help navigate bugs and drugs in a world where either can be good or bad depending on the context:

One of the unfortunate outcomes of the antivax movement is that it has created an environment where public health officials can’t say anything even moderately circumspect about a vaccine or people will lose their minds. Because while nearly all vaccines work gloriously, producing high and long-lasting protective antibody titers, I work on difficult influenza viruses for a reason.

Sidebar on Influenza Vaccines. I will spare you the complex immunology of influenza. But the upshot is that influenza vaccines are not stellar. They are safe and save lives. But they would save millions more lives if they worked as well as the (amazingly godlike) vaccines we have for other diseases.

So why don’t influenza vaccines work as well? It’s not the vaccine, it’s the virus. It evolves so quickly that it continually replaces its surface proteins, requiring new vaccine strains that match better. Because vaccine manufacturing takes at least six months, by the time the vaccine is available it’s often no longer a match.

But there’s another problem. Influenza viruses evolve incrementally over time in humans, but they can also jump from birds (or pigs) into humans, introducing entirely new viruses that humans have little or no immunity to. This is what happens during a pandemic (similar to COVID). When humans get exposed to lots of genetically different influenza viruses (and potentially vaccines) over time, it alters their immune repertoire and ability to defend against new strains. The first influenza strains you first encounter early in life affect what kinds of strains you they’ll successfully defend against for the rest of your life. It’s called imprinting. Let’s just say this made for some interesting conversations with my son’s pediatrician. We ended up giving my son the vaccine, but only because it turned out to be a bad flu season and I couldn’t jeopardize his short-term health just to wait until he was 2 so he could get a live vaccine that may or may not provide better imprinting in the event of a pandemic many years in the future. Thank god other vaccines aren’t as complicated as flu.

One last word on the economics of vaccines. If a corrupt drug company wants to make a ton of money on a scammy product, it would be optimal if that product was (a) easy to produce and administer, (b) something that people needed to take frequently, and (c) something where the side effects could be easily hidden. You can see why highly addictive opioids killing adults fit the bill nicely. And why vaccines given to babies once or twice in their lifetime would not. Pharmaceutical companies do like to make money. But no one wants to mess with moms.

In fact, vaccines were a money-losing operation for a long time until Bill Gates jumped into the game. He helped create new markets for vaccines in the developing world through programs like GAVI. Vaccine development is finally flourishing again and there are new vaccine candidates in the pipeline for RSV, norovirus, dengue, and even Lyme disease. Maybe round 2 will go better.

As far as the COVID vaccine goes, scientists will do everything in their power to develop and test a safe, effective vaccine. But the COVID response in America has become dangerously politicized. We already saw how the intense political pressure to expediently resolve the COVID pandemic led to government leaders promoting therapies that were unproven. The work of scientists and FDA regulators to run complex, lengthy clinical trials to develop and test a COVID vaccine must occur without political involvement or interference.

However, even if the world’s best and safest vaccine is produced, be prepared for a nasty fight over who is required to take it. Will schoolchildren be required to be vaccinated to attend public school? Will businesses try to mandate vaccination among employees? The COVID vaccine will soon be upping the ante on America’s culture wars. Russian trolls are licking their lips.

Then again, maybe a deadly pandemic is what’s needed to finally shake America’s vaccine hesitancy. America has not really seen what this bug can do yet. And after a long 2020 of America continuing to ‘err on the side of freedom‘, maybe the fight won’t be over who’s required to take the vaccine, but who’s first in line to get it.

TL;DR: Vaccine hesitancy in the US could reduce uptake of the COVID vaccine predicted to become available in 2021. Low uptake would could make it difficult to achieve 60% herd immunity and reopen businesses and schools.