COVID: Not the Great Equalizer

Futbol! As a possible sign that the apocalypse is not coming quite yet, Premier League soccer began in the UK last week. US star Christian Pulisic came off the bench to score for Chelsea. While wearing a Black Lives Matter shirt. Was this my reward for all those months of quarantine?

But as we celebrate the return of sports, as a harbinger of a world inching towards normalcy and reopening, we should take stock of what’s really embedded in America’s plan to take an increasingly large pool of employees back to work in the midst of a COVID pandemic.

Megan Rapinoe and Tobin Heath have decided not to play during the NWSL’s debut tournament this week, citing COVID. Who could fault them? But did the large supporting cast of workers who now have to mow the grass or the trainers who treat the injuries also have opt-out clauses? I would guess not.

A friend of mine pointed out the obvious double-standard in these Washington Post headlines. When a baseball celebrity questions the safety of work conditions it’s because he cares for his family. When teachers do the same thing it’s called a ‘revolt’.

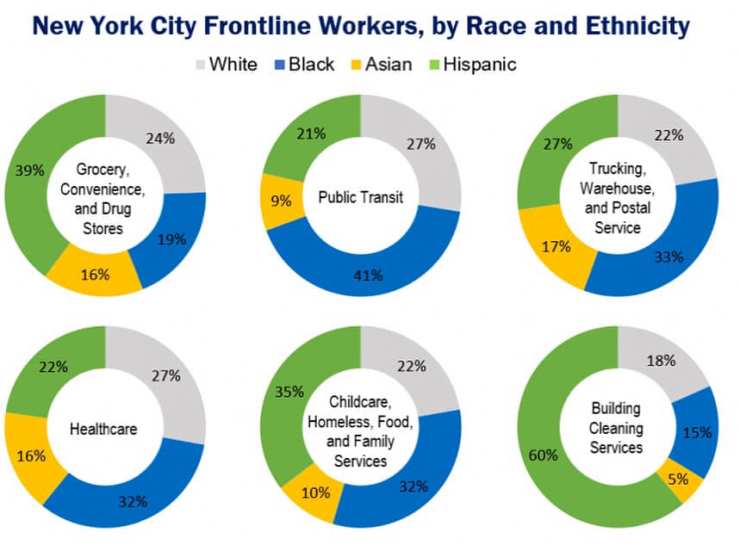

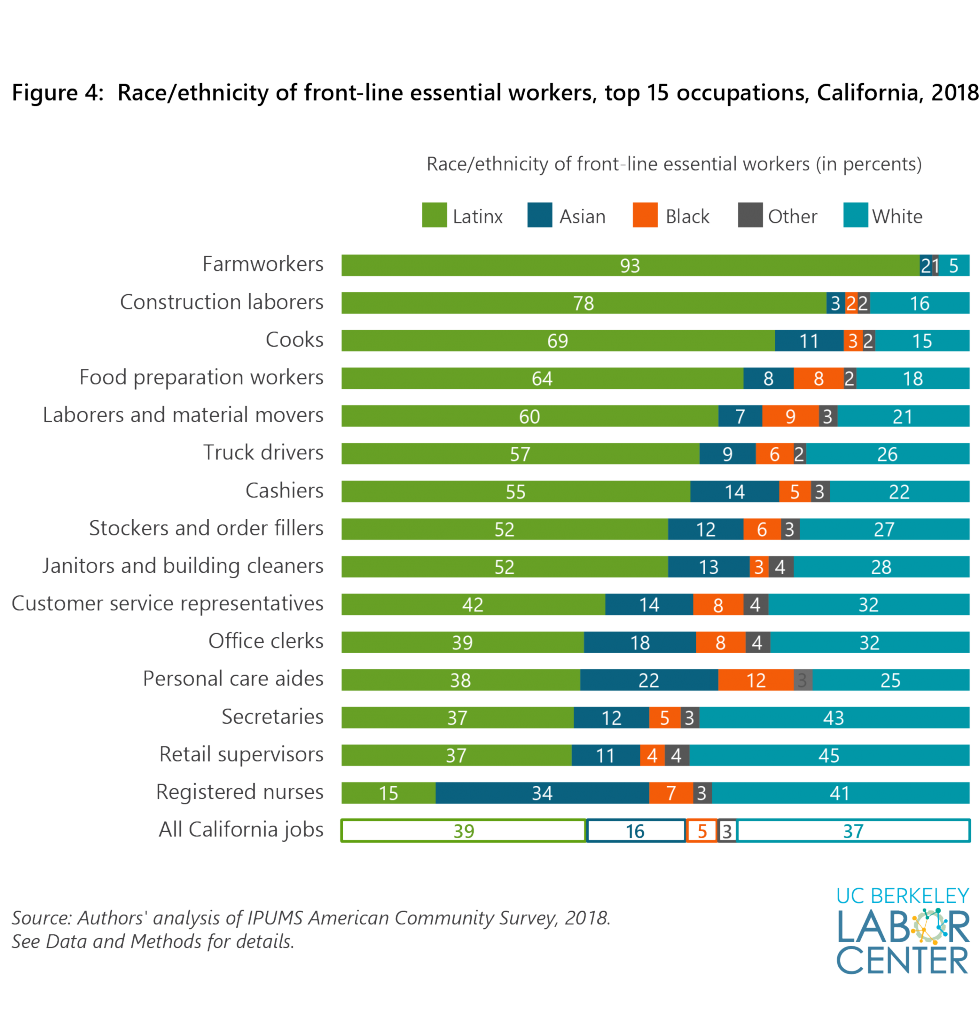

America is so inured to gross inequities in the health and safety of workers (health insurance and sick leave…cough, cough), that maybe this doesn’t even faze us. But it should. Particularly as white America goes through a reckoning around Black Lives Matter. There are stark racial disparities in the people who fill the tens of millions of essential service jobs in America. And they have cruelly shaped the death toll of the pandemic.

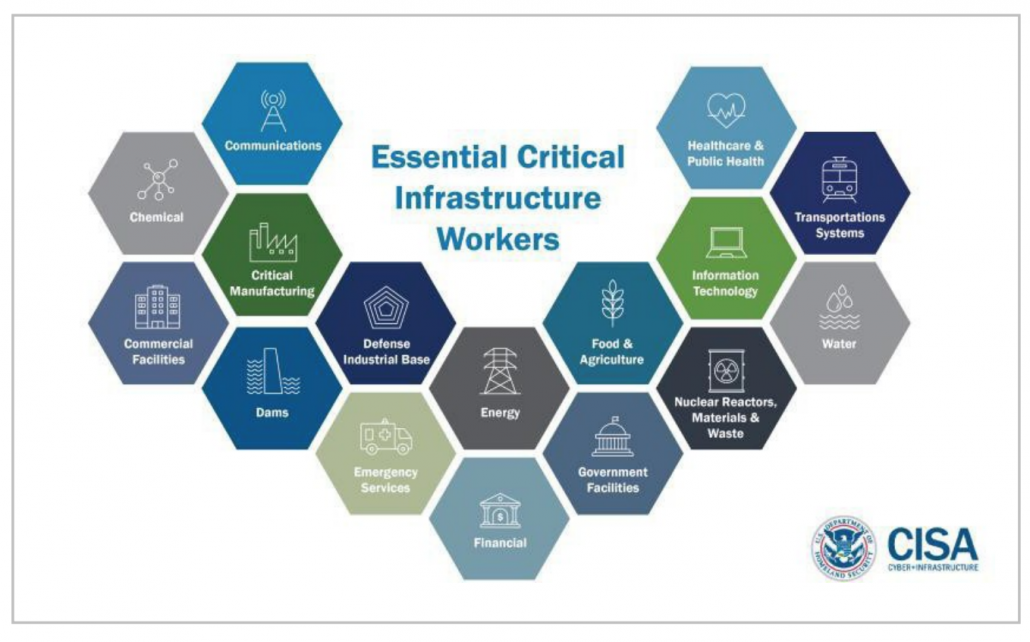

Disparities in worker treatment have been pronounced since the beginning of the pandemic. When COVID broke in March not everyone snuggled into their home office. The Department of Homeland Security made a list of all the business sectors that could continue to make their employees go to work. America’s Critical Infrastructure. The list isn’t short.

Because grocery stores still needed to sell food. Pig carcasses needed to be processed. Amazon packages needed to be delivered. Most employees were not given the choice to remain home to protect their families. Even when many live in smaller homes that make it difficult to isolate sick people and prevent spread to other household members. Some don’t even get sick leave.

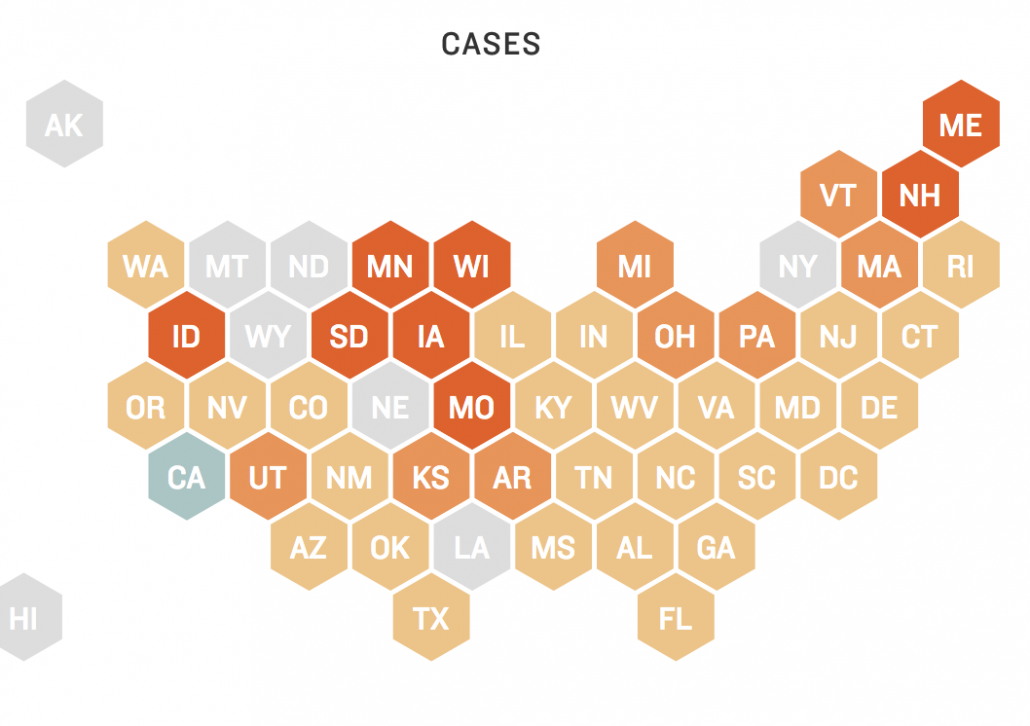

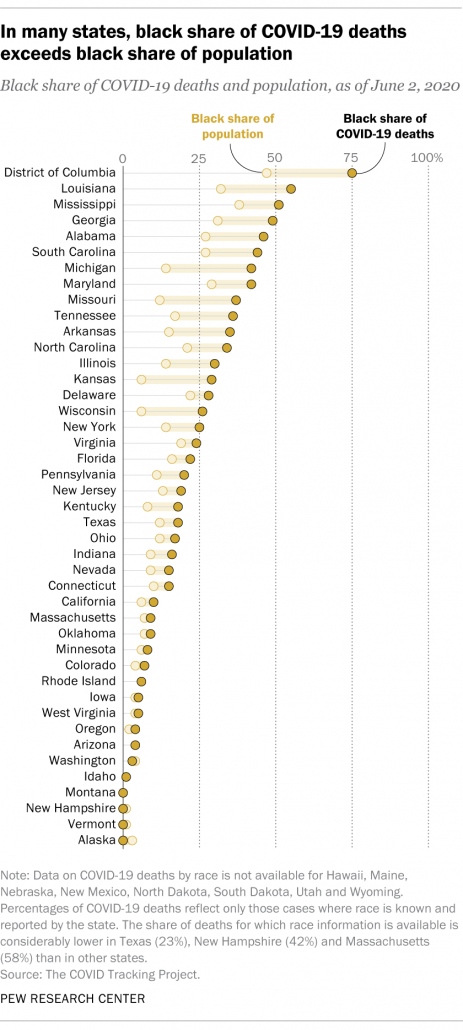

As I write this, African Americans are dying from COVID at far higher rates than whites. The reasons for this are not biologically complex. African Americans are more likely to be infected in the first place when they disproportionately work frontline jobs deemed essential to the country’s infrastructure. And once infected, African Americans are more likely to be hospitalized because they have higher rates of underlying health conditions, caused by long-term inequities in access to health care.

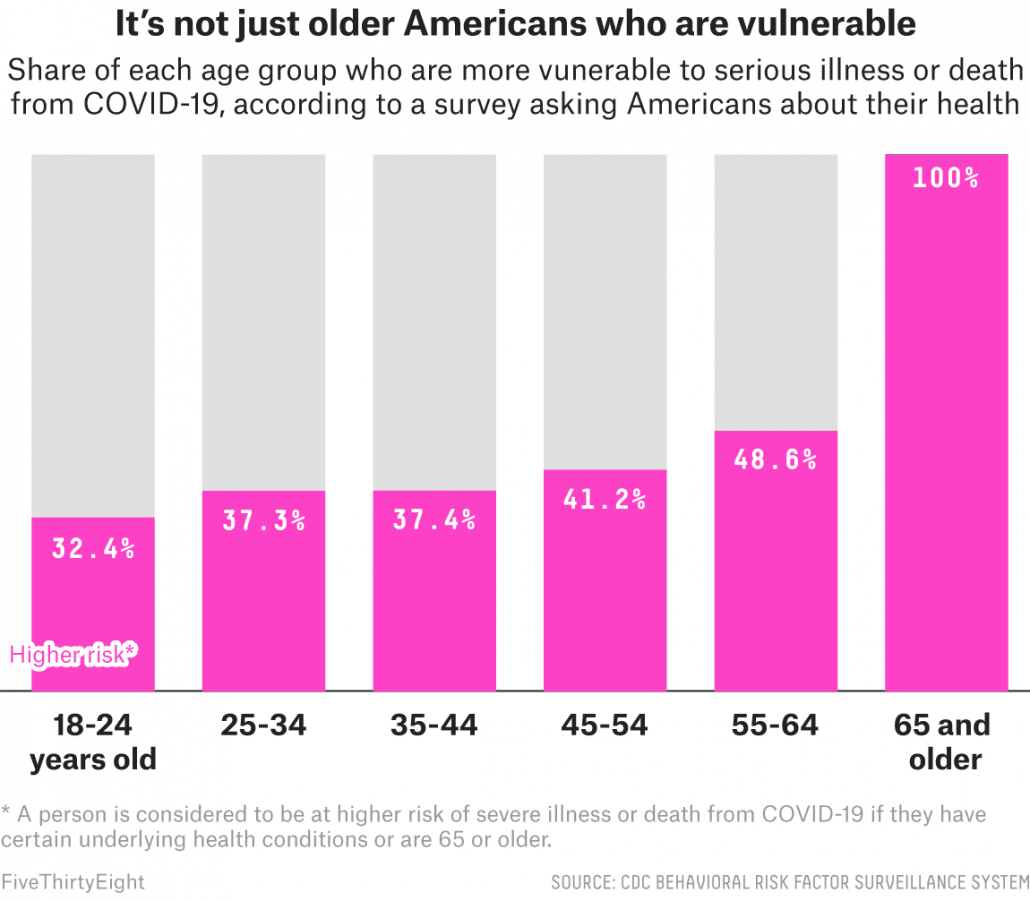

My early blogs (like March 12’s ‘Protect Granny‘) focused on how we needed to protect the elderly who were at higher risk of dying from COVID. That initial message came from looking at data from the world’s first major COVID outbreaks in China and Italy. But as the COVID epidemic played out in the much more racially diverse US, it has become abundantly clear that seniors aren’t the only ones at risk.

There are two main categories for COVID risk.

Risk Category 1: Getting infected in the first place. Many factors determine your likelihood of coming into contact with an infected person, including (a) occupational risk, (b) household risk (e.g., has spouse with occupational risk), (c) geographical risk, (d) age-structured risk (younger people have larger social networks), or (e) dumbass risk. Dumbass risk includes, but is not limited to, any act done to intentionally demonstrate a lack of fear of COVID. I’ve been taking numbers.

Risk Category 2: Needing hospitalization after getting infected. We are still figuring out exactly what predicts why certain people get severe disease and others a asympatomic. Age is the most important factor. But there are many younger people with health conditions that put them at risk. CDC just updated the list:

Chronic kidney disease

COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

Obesity (BMI of 30 or higher)

Immunocompromised state (weakened immune system) from solid organ transplant

Serious heart conditions (e.g., heart failure, coronary artery disease)

Sickle cell disease

Type 2 diabetes

There is also ongoing research trying to identify specific genes that predispose people to severe illness. There’s some evidence that a person’s blood type matters, with O being protective. There are also genetic mutations that cause sickle cell disease that are more common in African Americans and put them at higher risk of having complications if they get infected with COVID. But the major issue is that African Americas have higher rates of underlying conditions like type 2 diabetes and hypertension from long-term health inequalities and poor access to healthcare.

These risks are not limited to African Americans. Latinx and Native Americans also have the dual problem of higher occupational exposure plus underlying conditions that predispose them to worse COVID outcomes. The major narrative from government officials continues to be that we need to protect seniors. But the age profile for COVID deaths will continue to skew downwards as we get better at controlling COVID in nursing homes and expose more young people with underlying conditions as businesses reopen.

There are many things we could do politically to support essential workers who keep the country running. I encourage everyone to learn about these issues. But at an individual level we also can:

(a) Be aware of the double-standard between celebrities who opt out of work during COVID and other classes of American workers.

(b) Support essential workers asking for businesses and organizations to provide them with better protections against COVID.

(c) Support access to regular testing and healthcare for essential workers and their families, as well as prioritization for vaccine when it becomes available.

(d) Ask yourself whether there are adequate protections for the workers at businesses you frequent. Or the people who care for your children.

(e) Wear a mask to protect service providers you come in contact with.

(g) Continue to socially distance as much as possible. The less COVID circulating in the community the less infection risk for essential workers and their families who don’t have the opportunity (privilege) to socially distance.

(h) Understand that we are all in this together. If essential workers get infected, they could infect a spouse who works in a nursing home. They could infect their own children who attend your child’s daycare. We are all intertwined in a network of crisscrossing humanity. Recall that it was not long ago that Texas thought COVID was a New Yorker problem. Like it or not, America, we all mixed up in this crazy basket together.

TL;DR: African Americans are dying at higher rates from COVID due to higher occupational exposure and long-term inequities in health care.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] most. As a result, a substantial proportion of Americans still endure long waits, particularly in Black and Latino communities that are still being hit the hardest. This makes contact tracing impossible. To control outbreaks, people who are infected need to be […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!