Can Americans Win at Game Theory?

From childhood, I was determined not to become an economist. My father was an economics professor. So was his father, sister, and brother-in-law. I don’t know what other families talk about at the dinner table. My family talked about airline deregulation. My father was conservative, his relatives were liberal, and the same circular arguments about private sector versus government-led policies fell along predictable partisan lines with no one ever convincing the other of anything. Resolution was not the point. It was just politics for sport.

I rebelled and became a scientist, a novel career choice among five generations of Wechslers, Daums, Nelsons, and Palonens. RNA viruses had nothing to do with politics. I studied the genetic code of microbes found in humans and animals around the world to figure out how pandemics arise. On occasion when my father tried to rope my scientific opinion into a family debate on climate change, I would wander off into another room to find a cat willing to be pet.

Then in January 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic began. I tried for nine months to stick to science and medicine. But I found myself unable to fully explain America’s COVID situation without drawing on economics. Because as the COVID-19 pandemic wears on, America has become trapped in a very real prisoner’s dilemma. Until all Americans understand how the game works, everyone loses.

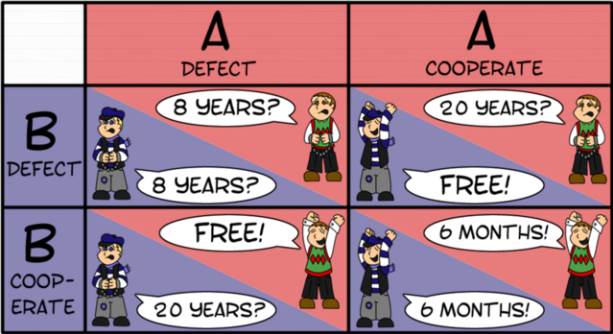

For those uninitiated with game theory, the prisoner’s dilemma is a situation in which individuals have an incentive to make a choice that does not produce the optimal result for the group.

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. They cannot communicate. The authorities cannot convict them on the main charge (20 years jail time), but they can on a minor charge (6 months jail time). If they both stay silent they get they both get the lesser 6 month sentence charge, the optimal result between the two of them.

But, if one speaks out then that person is released, and the other person is put away for 20 years. The incentive is for both to betray the other, in the hope of getting a reduced sentence, but which results in them both getting a medium sentence (8 years jail time). The implication is that two individuals acting in their own interest reach a suboptimal outcome.

Suboptimal outcomes occur all the time because individuals and countries are prone to acting in what appears to be self-interest, whether in missile defense, NASCAR racing, auction bidding, or in business. Cooperation can halt arms races and achieve the most optimal outcome for all, but requires international treaties, state laws, or industry-wide agreements that create rules or systems that incentivize cooperative behaviors.

For example, a fisherman has an incentive to harvest as many tuna as possible each year. But if every fisherman overfishes, the entire stock becomes depleted and everyone loses money in subsequent years. Instead, if every fisherman agrees to limit their annual catch, the tuna population thrives and everyone earns more money in the long run. A collective strategy is needed, either by industry self-regulating or by government setting catchment limits, to produce the highest earnings for everyone.

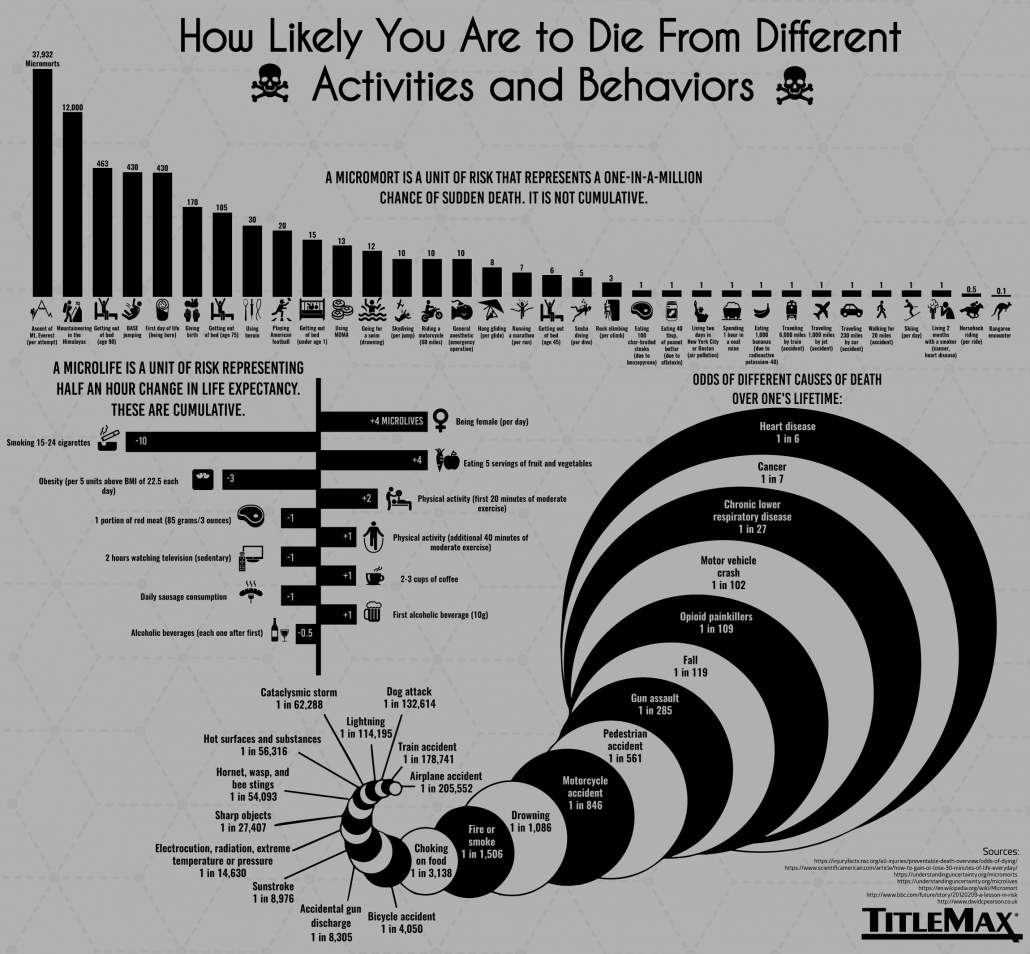

How is the COVID-19 pandemic an example of prisoner’s dilemma? Because most individuals do not have a high risk of dying. A young individual with no underlying health conditions could reasonably look at the odds of severe disease and conclude that they accept the risks and wish to host parties, attend rallies, forego face masks, and travel to visit family over the holidays.

But if everyone ignores recommendations by public health officials, COVID-19 transmission would quickly skyrocket, large numbers would die, including younger people, and businesses and schools that were previously open would need to close. Presenting COVID-19 as a personal choice and an exercise in individual risk assessment produces a sub-optimal result for everyone. A better strategy would be if everyone collectively, like the fishermen, agreed to incur a reasonable limit on their behavior, even if it is not immediately in their self-interest, with the understanding that it would produce a higher return for everyone, including themselves in the long run, by containing virus transmission below a certain level and sustaining a national economy.

Certainly there are barriers to implementing such a strategy in the real world. For one, how do you induce Americans to act towards an optimal outcome when scientific information has been misconstrued and there is no nationwide agreement on the scale of the pandemic threat to begin with? You can’t expect the actors in the prisoner’s dilemma to cooperate if they believe jails are just a hoax designed to scare people.

But even if the optimal outcome cannot be realistically achieved in today’s political climate, there is still value in understanding the concept of prisoner’s dilemma and why a ‘personal choice’ approach to COVID fails everyone. Principles of game theory help explain why families should not travel over the Thanksgiving holidays, even if they accept the personal health risks. Or why everyone can enjoy more freedoms, such as participating in outdoor running events or in-person kindergarten, if everyone cooperates and accepts a reasonable set of limitations, such as refraining from mass indoor gatherings, to keep the virus in check.

Because of superspreading events, 20% of COVID cases contribute to 80% of transmission events. As a result, a realistic approach to COVID control may not be convincing 50% of the population to lockdown stringently (>80% change in behavior), but instead convincing >95% of the population to change their behavior 30%, focusing on avoiding large gatherings (e.g., rallies, weddings, funerals, church, parties) that spark superspreading events. In the context of game theory it makes sense that all individuals accept limitations on behaviors associated with superspreading events, regardless of their personal risk tolerance for other activities, such as riding motorcycles, skydiving, or smoking.

A game theory framework does not require people to ignore individual risk altogether. Seniors and those with underlying conditions may opt to limit their exposure even more stringently. The key point is that individuals should not behave only according to their personal risk. A little knowledge of game theory could help people reconcile seemingly conflicting messages of COVID is a risk I’m willing to accept with But it is still in my interest to cooperate with reasonable public health recommendations.

Understanding how COVID relates to game theory also explains why face masks may be just as important for promoting societal cooperation as in reducing disease transmission. In a pure prisoner’s dilemma situation, the prisoners cannot communicate with each other or telegraph any intention to cooperate. However, in the real world people openly communicate their COVID decisions. Wearing face masks has become a powerful way for an individual to telegraph their adherence to public health guidance and reinforce cooperation across a community. Sustaining motivation to limit behavior can be difficult without ongoing reinforcement and confidence that others are also making similar sacrifices.

Admittedly, a face mask is not a perfect indicator of an individual’s COVID behavior. A person could wear a face mask in public and hold large transmission-friendly gatherings at home. But the face mask has become an important way to signal to community members that others are sacrificing for the greater good. I have to acknowledge that as a hard-numbered scientist I have focused on face masks purely from a disease transmission perspective. At times I have undervalued their societal importance in promoting cooperative behavior. As I said, I’m a scientist, not an economist. But I am accepting that it will take more than science to save America from COVID.

Understanding game theory may also help understand why America has more COVID deaths than any other country. Americans value a form of rugged individualism that is great for cinema and entrepreneurship, but a major disadvantage in controlling COVID. Globally, we have ongoing natural experiments in how countries with different cultures and governments succeed or fail against COVID. Countries that have successfully contained COVID tend to have deeper cultures of cooperation and deference to authority, such as Canada, Denmark, Rwanda, Singapore, South Korea, and China.

But game theory should give Americans hope. With the awful 2020 election finally in our rearview mirror, now is the time to reset. Right now many Americans, particularly conservative-leaning, still view COVID public health recommendations as intrusive and paternalistic. Public health officials focused on averting deaths still find themselves pitted against economists focused on preserving jobs and avoiding the costs of lockdowns. Public officials must offer a more coherent and persuasive strategy than media-inflamed fear tactics. We must find new ways to incentivize people to incur a degree of inconvenience and delayed gratification, even if it’s not in their immediate self-interest, because they understand why.

Another way to understand game theory involves jellybeans. Four people sit at a table with a bowl in the center and every minute the number of jellybeans in the bowl doubles. Anyone is free to take jellybeans from the bowl at any time. After a certain time period (which the players do not know) whoever has the most jellybeans wins. Doesn’t sound like a complicated game, right? But there are multiple conflicting incentives. Every time a person takes a jellybean they (a) incentivize others to take jellybeans and (b) reduce the total number of available jellybeans. Instead, if players all refrain from taking jellybeans while they double and double, then a huge number will start to overflow in the bowl that everyone can indulge in. Perhaps elected officials should have to play the jellybean game before they are allowed to take America out of international nuclear arms treaties.

The jellybean game is similar to COVID because both systems involve exponentially growing populations that require discipline early on, with reward coming later. Instead of refraining from jellybeans, if Americans could refrain from bars, parties, and other gatherings during early signs of the virus taking off in a community, everyone could indulge later. So how do we convince Americans to refrain from grabbing the jellybeans during that critical early window so they can feast later on? I don’t know. I’m tapped out. Ask a real social scientist.

Very interesting article. I was trained in political science, and I have a keen interest in game theory, so this approach to “messaging” appeals to me. What interests me is how a sensible game theory approach to the pandemic has collided with a rights-based discourse on the political right. One could write quite a bit about the irony of this appeal. After all, isn’t it the “libs” who promiscuously manufacture “rights” in order to thwart community consensus and commerce?

The invocation of game theory has another advantage: it gives us an enemy–a cunning resourceful enemy. With my students, I use the metaphor of a video game. We must now play a vastly complex and multi-layered game against a brand new “Boss.” Are we up for the challenge?

Once again, thank you for your article.