How the West Was Lost

Question: Why does the Bible command us to Be Fruitful and Multiply?

Answer: Because half of the kids weren’t going to see their fifth birthday.

For the last 10,000 years of human history, and as recently as my grandmother’s generation, children grew up with foundational experiences that included death of friends and family by infectious agents. Growing up in Boston in the 1930s, my grandmother was infected with tuberculosis as a teenager, along with her father. After witnessing her father’s death, she spent two harrowing years in a sanitorium for TB patients watching her friends get picked off one by one.

Our grandparents’ generation grew up with an intuitive, common sense understanding of infectious disease risk that modern Westerners sorely lack. Citizens can mobilize rapidly to to existential threats that are familiar: Israelis to terrorism, Japanese to tsunamis, or post-SARS Hong Kongese to pathogen outbreaks. No one in the West wants to return to an era when Little League also included funerals. But by growing up in sanitized environments, modern Westerners have lost not only their fear of pathogens, but an intuitive sense of how to respond to infectious disease threats that has caught us badly flatfooted during COVID. And now that COVID is here to stay, our inability to intuitively evaluate the risk of invisible bugs is highly problematic, sending us flailing from one reactionary extreme to another, from mask-shaming joggers to group protests against social distancing restrictions.

Stark differences in familiarity with infectious disease risk aren’t just divided generationally by time, but also geographically over space. My aunt recently did a clever survey of her friends, asking them to guess the answer to this question:

My New England seaside town Gloucester has 30,000 people and 15 confirmed deaths from COVID-19 so far. My daughter lives in Rwanda, a country with 12.8 million. How many deaths has Rwanda had?

No one guessed the right answer: zero. The trajectory of COVID-19 within Africa is highly bifurcated between countries that responded early and decisively, and those like Tanzania that sat on their hands. Well-governed countries like Rwanda have succeeded remarkably in containing the virus early through swift, stringent lockdown. Because swift, stringent lockdown is exactly what differentiates the COVID winners (New Zealand, South Africa, South Korea, Israel) from the COVID losers (US, UK, Brazil, Italy, Russia). It’s why there have been more deaths in Connecticut than in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Vietnam combined. You know what happens when you win at COVID? Ask the New Zealanders. You get a dream world in which you go back to flipping pencils in the office while your kiddos go back to school. You get to not tank your economy.

Why was Rwanda better prepared for COVID than France or the United States? Isn’t the West supposed to be the standard bearer when it comes to international disease crises? Wasn’t it just a few years ago that US CDC was the one bailing out Africa during the Ebola outbreak?

The US has vastly more wealth and technology, but Rwanda has something proving to be more important. You could call it citizen mindset or infectious disease IQ. Not only do Rwandans need to manage endemic malaria, but also sporadic flare-ups of Ebola in their neighbor the DRC. Throughout the developing world, people regularly contend with a range of pathogens for which there is no vaccine available: Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis), Llasa fever, Japanese encephalitis, chikungunya, dengue, Rift Valley fever, Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever, Nipah, sleeping sickness, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis. Throw in the pathogens Westerners have actually heard of like HIV, measles, SARS, and malaria, and you realize why cultures spanning most of the non-Western world know a thing or two about bugs.

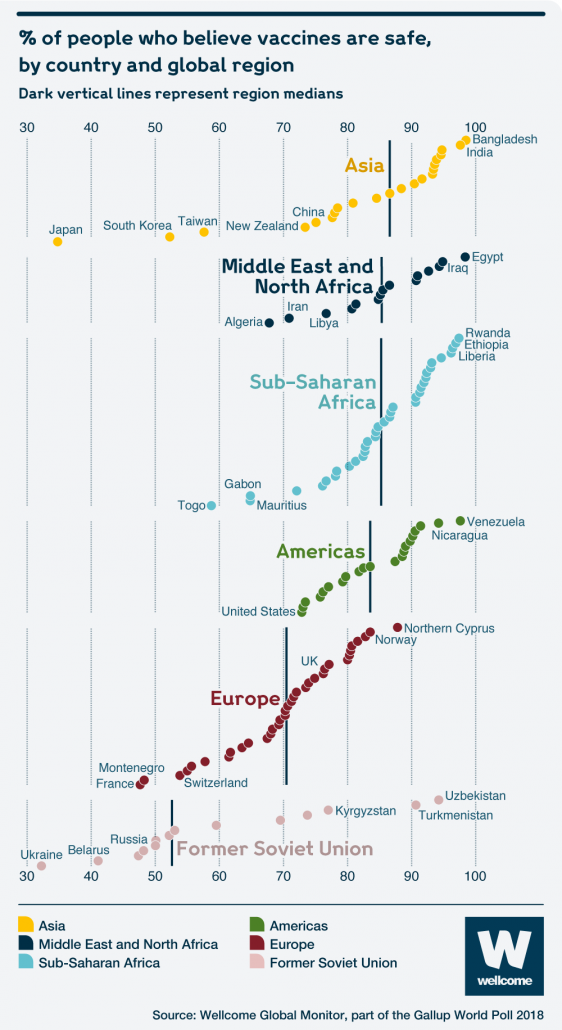

What happens when the generations currently residing in the West are the first in human history to be raised in a bubble that doesn’t include regular experiences with infectious disease mortality among the young? Soccer moms in Orange County start refusing to give their kids the measles jab. Knowledge of infectious disease atrophies like a vestigial limb. France may have the Sorbonne, but its citizens score 40 points lower than Nicaragua in response to the question Do you believe vaccines are safe?

and South America in vaccine trust.

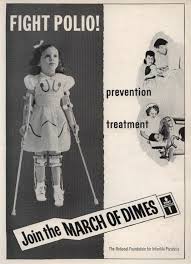

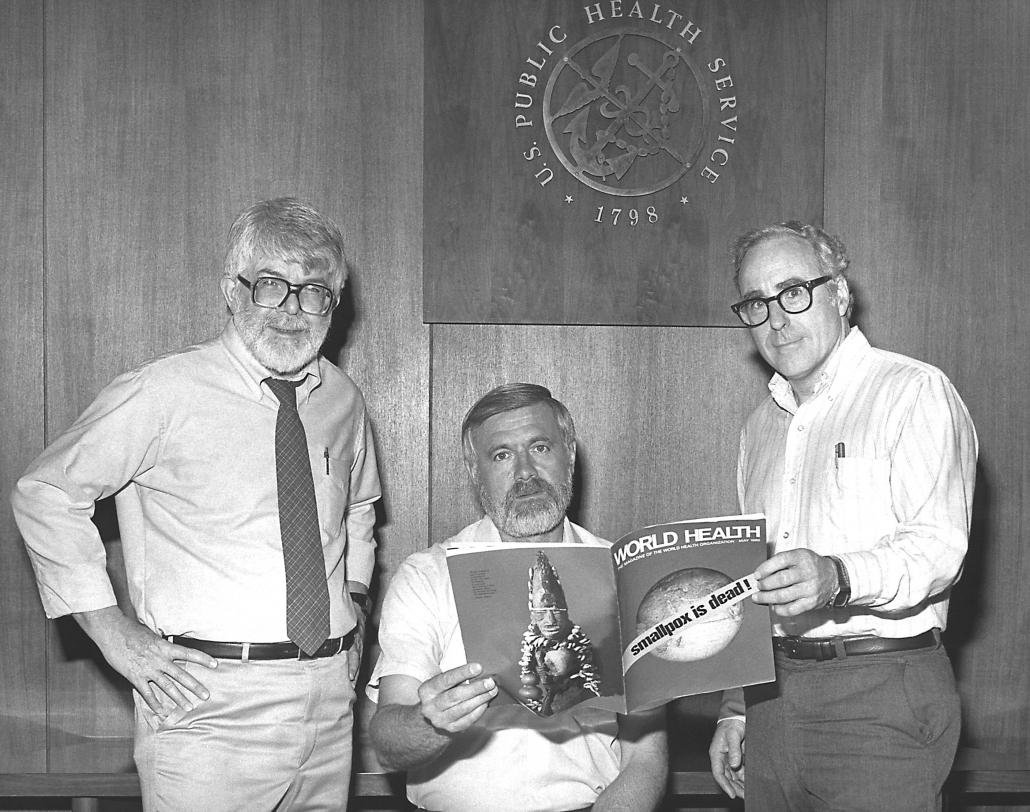

How did Western society do a 180-nosedive from the March of Dimes to anti-vaxxers in a single generation? Of course we know who’s to blame: Barack Obama. Funny joke, right? Well, there’s actually an underlying grain of truth. The reason why Americans and other Westerners have lost their intuitive sense of infectious disease risk is because Western governments and research institutions in the latter half of the 20th century were too effective in achieving victory after victory against the world’s deadliest pathogens . In the 1970s we wiped one of the deadliest pathogens (smallpox) off the face of the earth. A CDC-led team had to track the final cases hidden in the remotest corners of the Earth. Only Indiana Joes or superheroes in capes are supposed to do stuff like that.

For decades the US has been undisputed leader in global outbreak response. GW Bush is no favorite of the left, but his PEPFAR program gets enormous credit for delivering antiviral drugs at scale in sub-Saharan Africa and turning the tides of an HIV epidemic that was spiraling out of control. CDC was critically involved in helping countries in West Africa control their Ebola outbreaks, and more recently in the DRC, using a new Ebola vaccine developed at the US NIH.

Why did a nation with a legacy of fighting the rest of the world’s infectious disease problems fail to control COVID within its own borders?

Countries with higher GDPs still have a lot of advantages against COVID over the long run. We’ll develop a vaccine faster and have the funding to administer them at scale to our citizens. We’ll discover drugs that reduce disease severity, and churn those out as well. I’m no expert in finance, but the US seems to have a miraculous bottomless bank that creates trillions of dollars out of thin air so we can sustain social distancing without collapsing the economy.

But vaccine is a long way off, and SARS-CoV-2 was doing loops around the world at a time when all we had in our toolkit was human intelligence and willingness to mobilize. Government leaders needed the knowledge and foresight to swiftly grasp of the scale of a new disease threat and understand that the only way to contain the pathogen was through strong, early decisive lockdown, despite economic consequences. And citizens needed to consent. With less experience in managing infectious disease outbreaks than humans from any other time or place in history, the West simply could not mobilize in time.

In early March, when COVID was appearing in Europe and Asia but didn’t seem to have a foothold yet in the US, I had a conversation with my aunt from Gloucester, MA. She knew the city’s mayor personally and wanted expert advice. I told her just to focus on 3 things: (a) build testing capacity, (b) make plans for nursing homes, and (c) cancel large gatherings before the first case is detected. With a highly capable mayor in a small city with a longstanding culture of social welfare, I thought Gloucester, MA could be a model for US COVID response, and possibly avert a single death.

But it turns out it takes a lot of guts for government leaders to act preemptively to COVID. Americans know the drill when it comes to responding preemptively to hurricanes and natural disasters. Local leaders don’t have to sit on their hands and wait for the breeze on their cheeks before ordering an evacuation. But Americans have no experience with responding preemptively to invisible bugs lurking at their borders. You might as well have said space aliens were coming.

At face value, the upcoming months of relaxing lockdowns in the West should bring sunnier skies. However, reopening society would be smoother in a population with a better grasp of infectious disease risk. By their nature, humans have inherently flawed perception of risk. We tend to be afraid of anything considered foreign or exotic (like terrorists or sharks). But risks of familiar activities rapidly become normalized (like car accidents).

We are not aware of how rapidly we have normalized our sense of COVID risk. This is an actual conversation I had with a highly intelligent person:

Highly Intelligent Person: I’m going to join an outdoor group exercise class.

Me: Sure, if you feel comfortable. But you recognize that the risk here hasn’t actually changed much since a month ago? Not here.

Highly Intelligent Person: Well, I’m feeling a lot more comfortable having made it this far without getting infected.

Me: Yes, but you got this far because you social distanced.

Many of us are feeling pretty good about COVID. It’s become less scary. Our inner circle of friends and family probably haven’t been infected. But we need to be highly aware of how rapidly we normalize risk. And particularly how we bias our perception of disease risk. We still think we’re going to get infected by sink in a dirty public bathroom, not by our gorgeous wife.

And we need to realize that no matter how much New York Times we read, very few of us have an intuitive sense of how and where viruses transmit. To make it worse, we’re horrific at statistics. It’s not out fault. For some reason we have never updated our 1950s math curriculum that makes you take geometry and trig and maybe some calculus to get a high school diploma, but not a whiff of stats. The one damn thing in school that might have been useful.

While this post gives a mile-high view on why some the richest and most educated countries in the world have been the least equipped for COVID, there’s still a lot of guidance needed on the ground. Here’s my rapid-fire take on a couple burning issues:

Antibody tests. Everyone and their dog wants to know if their recent or distant cough meant they were infected by the virus. Detecting antibodies in the blood can theoretically tell you if you’ve recovered from a SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antibody tests are going to be crucial for assessing how many people in a community were infected from different age groups, and how many never experienced symptoms. These surveys will be helpful in assessing the role of children in transmission and the risks associated with reopening schools in the fall. But I’d be skeptical of serology tests being used to assess individual-level infection histories. The tests can be inaccurate (false negatives, false positives), particularly new serology tests that haven’t been completely validated. Statistical methods can account for these inaccuracies when pooled over a population, particularly when combined with PCR data. But I wouldn’t expect antibody tests to be particularly meaningful for individuals.

Mutations. You’re going to hear a lot about the blasted mutations. Yes, viruses evolve rapidly and the viruses circulating now have genetically drifted from the original strain that emerged in Wuhan in December. But if a country/region/city wants to explain to its citizens why COVID is exploding, they either need to admit mistakes or explain complicated statistics around stochasticity and random super-spreading. A far simpler strategy is to look at the viruses you observe locally, notice that there’s a new mutation, and blame that. But the vast majority of mutations will have little phenotypic affect. And it’s perfectly expected to observe new mutations crop up wherever the virus sustains transmission locally. For some reason people find mutations scary, so the media bites everyone time. Mutations are not scary. If it weren’t for mutations we would all be clones of our parents. Now that’s scary.

Yelling at runners not wearing masks. To Wear, Or Not to Wear. That is the Question that seems to be gripping American communities like no other. It’s silly. The science just isn’t there one way or the other. Ask the hamsters. If you personally like wearing a mask because you think there’s a chance it’s helpful and at very least it telegraphs to the world that you take COVID seriously and consider yourself a socially responsible citizen, then wear your mask with pride. If you don’t like wearing a mask, and are in a setting that doesn’t require it, don’t feel guilty. Focus instead on other kinds of running etiquette, and giving advance warning and lots of space as you pass. The key to COVID running is to not be such a hurry. Be prepared to slow down stop in your tracks entirely to let someone pass safely. Trust me, you’re not training for any races~

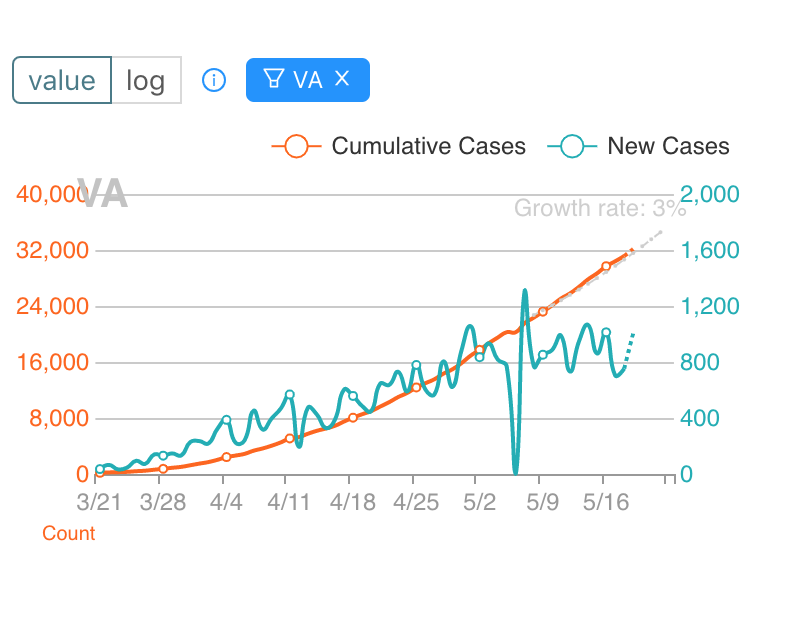

Should we be reopening? A big source of confusion is COVID risk is highly variable across the country. My brother lives in Burlington, VT, where there’s barely been any COVID and it makes complete sense to begin reopening businesses. But reopening needs to be data driven. Not motivated by politics or social distancing fatigue or a conviction that cold viruses simply can’t transmit when it’s hot and humid (just ask Singapore). So it’s important to understand what’s happening specifically in your community. You can find information on local health department websites. I find this site to be useful for state level trends. Here’s an example from Virginia, where there is little indication of cases coming down at a state level. At best the peak has simply leveled off.

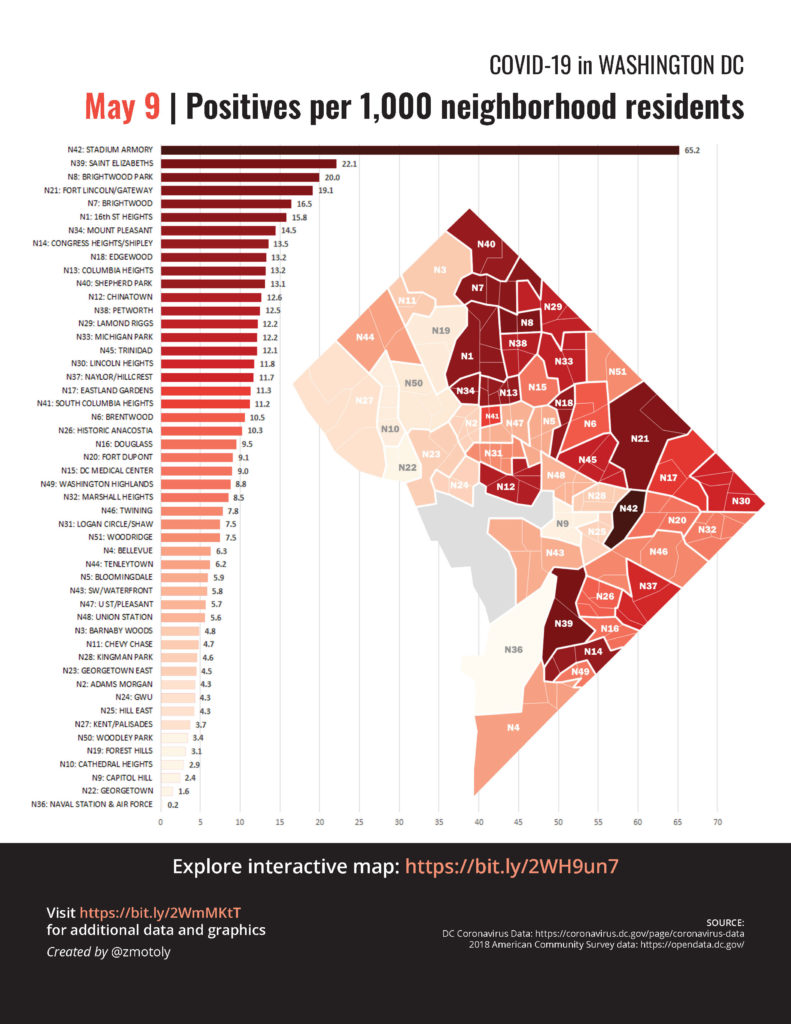

There’s also high variability within a city. Here’s DC by neighborhood:

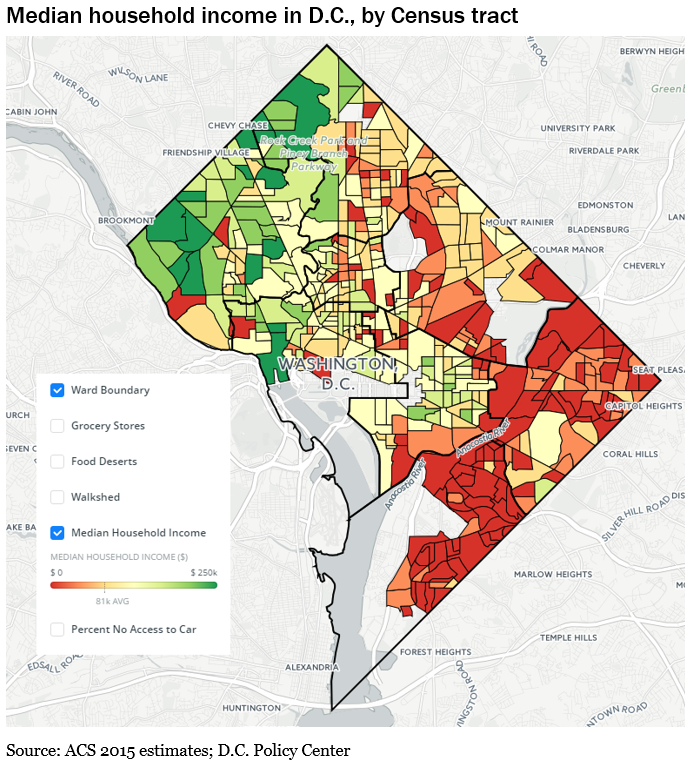

You’ll notice that COVID cases tend to crop up in lower income neighborhoods where people often have to report physically to their jobs, whereas higher income neighborhoods have more options for teleworking.

What began as a disease of the wealthy (travelers returning from cruises and Austrian ski vacations) is now evolving into a disease of the poor and neglected. The new epicenters will be in impoverished Indian reservations, prisons, slums, poorly run nursing homes. The virus is opportunistic and will exploit the vulnerable, especially where densities are high. Targeting such corners for disease control and testing is not merely altruistic. They provide breeding grounds for viruses that can reseed outbreaks in other settings and locations.

Monogamous Friendships. My chief advice for people who want to dip their toe into a world that includes (gasp!) friends is to approach it methodically and stepwise. In the upcoming months, I think it’s reasonable to make a single, highly selective step in expanding your contact bubble. Just for your own sanity. But think about which friend not only is someone whose judgment you really trust, but also someone who really matches you and your family in terms of risk profile. It needs to someone you’re so comfortable with that you can ask direct questions about their private habits and contacts. Because you’re putting the lives of your family in their hands. So you need to know if someone in their family must report physically to work. Or has a medical condition that requires visiting doctors. Or if they have to rely on babysitters for child care. Ideally they have similar shopping habits. And when you identify someone you are confident is a perfect match, be completely frank about offering a couple weeks of ‘monogamous’ friendship where you occasionally visit each other but agree not to see any other friends. Otherwise your contact network grows exponentially, since each contact has their own set of contacts. After a couple weeks or months you can swap and choose a new monogamous friend. But don’t cheat~

Thank you, Martha, for the importance of understanding history and science.

Very well done. But I find the maps confusing. My neighborhood (Takoma) isn’t identified, and it’s tough to pin down its location from these maps, but my Ward (4) has the highest number of cases, though it’s not the lowest income. The second map shows 2 areas in the northern part of the ward as green (high income), while the same general area is maroon (highest number of cases), so I’m not confident about your generalization regarding income, even though it seems logical. (If DC has this information by zip code, I can’t find it, though it too may not be helpful.)

Just because there is an association between income and COVID doesn’t mean there won’t be certain neighborhoods that are outliers in either direction. The data is also aggregated by ward (https://coronavirus.dc.gov/page/coronavirus-data) if that’s easier. An association between income and COVID was also seen in NYC neighborhoods. But it’s a good point that population density also varies by neighborhood and could be influencing neighborhood COVID patterns, not income alone.

Thank you Martha. Very well written.