COVID and Schools: Will It Work?

Low COVID infection rates of children combined with other countries reopening schools have made US officials bullish about sending kids back to the classroom this fall.

But the question Should schools open? may not be as important as Will they stay open? Recurring outbreaks in a school district could mean a return to online learning exclusively. The hard truth is that no matter how determined parents, government officials, and administrators are right now to open classrooms this fall, schools will close if there are major outbreaks in schoolchildren and teachers, as has occurred in many countries.

Israel presents a cautionary tale. Two weeks after reopening schools in May, 116 students and 14 teachers were infected at a single middle school/high school, leading to the closing of all schools and a curtain call on the country’s jubilant reopening. It raises the question: What are the prospects of US schools actually staying open this fall?

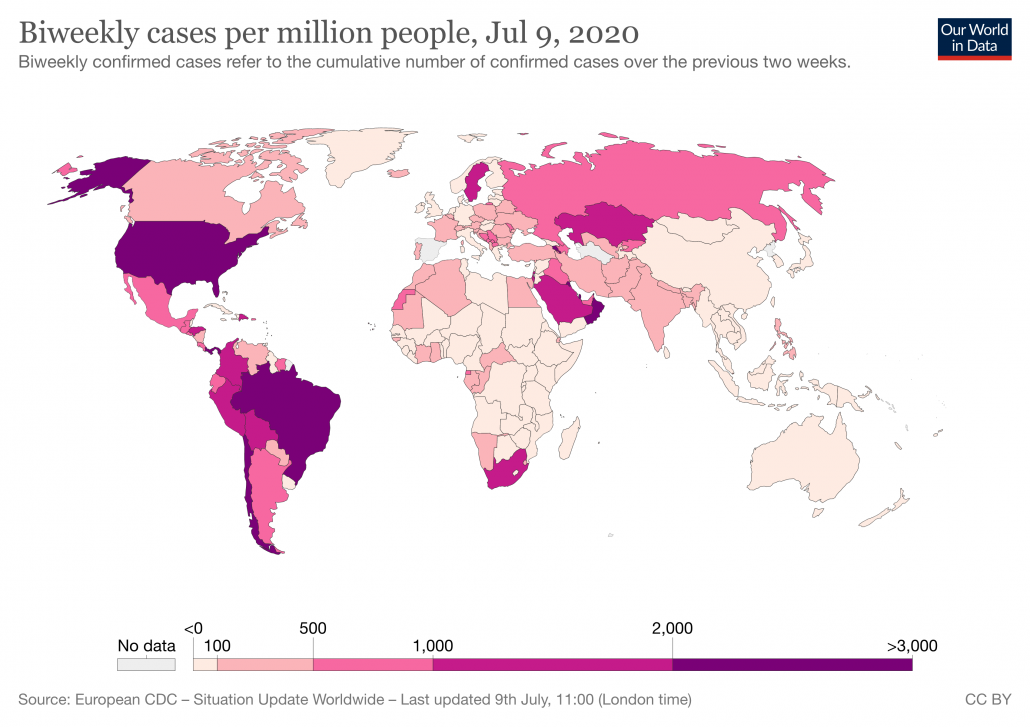

The answer depends a lot on where you live. If you open two schools today with the exact same protocols in Vermont and Florida, the Vermont school will have a much higher likelihood of avoiding outbreaks and still being open two weeks later. It’s simply a numbers game. Vermont had 16 new COVID cases last week. Just 0.8% of VT tests returned positive for COVID. This rate is similar to countries in Europe and Asia that have been able to open schools (Denmark, Norway, Germany, UK), which all have less than 1% of COVID tests positive. In comparison almost one-fifth of tests in Florida are positive for COVID right now. A school in Florida that tries to open up right now will be bombarded with index cases coming in from the community. The more index cases, the higher the chance that one of those kids will turn out to be a superspreader.

Can’t they keep COVID out of the school with daily screening? The problem is that kids tend to be asympatomic. If you’re not testing kids for live virus and only doing screening based on temperature checks and reported symptoms you’re going to miss a lot of silent cases. The problem is compounded when asymptomic kids transmit to other asymptomatic kids, creating chains of silent transmission that don’t get detected until someone (student or teacher) finally comes down with symptoms. A recent outbreak of COVID at a YMCA summer camp in Georgia, despite all counselors and campers passing all mandatory screenings, shows just how hard it is to keep the virus out of a group of kids.

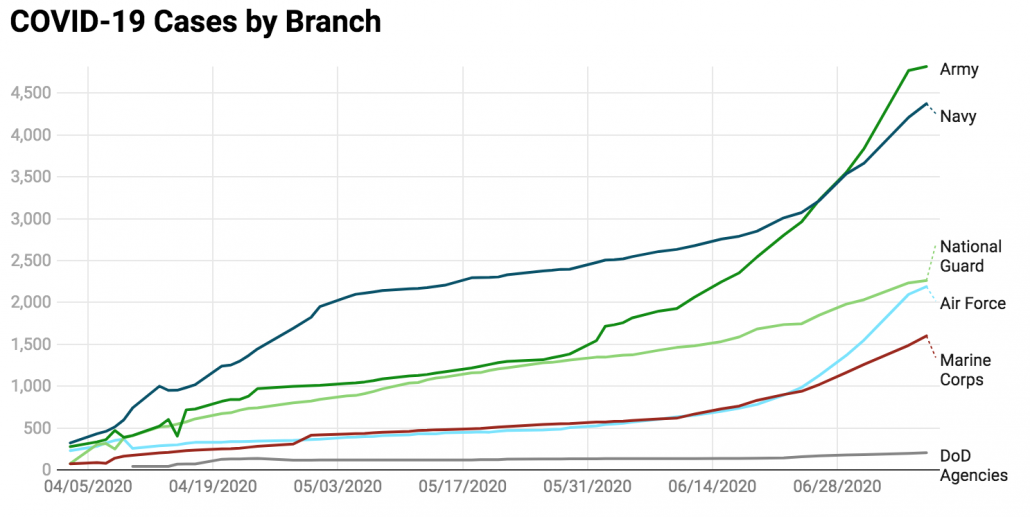

Won’t face masks and social distancing keeping the virus from transmitting between kids at school? Schools will do everything in their power to keep viral transmission limited within their classrooms, including smaller class sizes, limited mixing, social distancing, and trying get kids to wear masks. For better or for worse, there will be an enormous amount of Lysol. But let’s be realistic: a COVID plan that rests on teachers keeping schoolchildren physically distanced from each other at all times and with their masks is a plan with a lot of holes. Summer camps have already closed after COVID outbreaks in Missouri, Texas, and Arkansas, despite social distancing, masks, and mandatory quarantines before arrival. You think we can keep COVID from transmitting in kids? We can’t even control COVID in military units.

Ventilation in schools is also a vulnerability. Especially as there is growing concern by scientists that airborne transmission by fine aerosols has been underestimated, particularly in settings with close contact and poor ventilation. Notably CDC’s lengthy guidance for schools lacks any recommendations to move activities outdoors, which is logistically challenging but probably the most effective way to reduce transmission among schoolchildren, especially by aerosol.

Teachers also won’t have a potent weapon in the arsenal against COVID: testing. Professional athletes get routine COVID testing because it’s so important to catch index cases immediately before they spread. (Although there have been testing failures even for pro baseball players). US soldiers get tested before they go to bootcamp. Right now routine testing of schoolchildren in any capacity isn’t even on the table. Even in areas hardest hit by COVID.

This is terrifying. Maybe I shouldn’t send my kid to school after all. The overall health risks for children are low compared to the enormous benefits of in-person education. Kids are not at zero risk for severe COVID disease. The multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) has appeared in dozens of US children infected with COVID. And if schools open and more kids get infected there are certain to be deaths, particularly among teenagers. It’s just a numbers game. But children (unlike adults) may be more likely to die from influenza and other diseases acquired at school than from COVID. According to CDC data there have been 21 confirmed COVID deaths in children ages 1-14 in the US so far. As comparison, 185 children (<18y) died of seasonal influenza last winter.

COVID is not the only disease that is more severe in adults than children. Measles, mumps, rubella, and chicken pox are also, for various reasons, more severe in adults than in children. Kids and adults may have different distributions of the ACE2 receptor that the SARS-CoV-2 virus attaches to on host cells. We have a long way to go in understanding how young people’s less-developed immune systems respond differently to COVID infections than adults. And this remains a critical area of ongoing research.

So what’s all the fuss about? There’s a lot we still don’t know about how kids fit into the bigger picture for COVID transmission. Will schoolchildren take the virus home and infect higher risk parents and grandparents? Will outbreaks in schools spill over into the community? Are we setting up schoolteachers to be sacrificial lambs, especially as a substantial number of teachers are older or with conditions that put them in COVID risk groups?

Preliminary data suggests that kids are about half as likely as adults to get infected in the first place. And far less likely to get severe disease. But they a lot more contacts. And infected kids do shed virus at high levels and some studies suggest they transmit to other people efficiently, perhaps as well as adults. But scientists bemoan the lack of data needed to answer these big questions.

Sweden was a real missed opportunity to study COVID transmission in children. The country kept schools open all spring but never collected the data needed to study transmission chains. Preliminary findings in Sweden suggest that around 5% of kids 0-19 had antibodies to COVID, compared to 7% of adults 20-64.

New data on kids and COVID could also come out of the US this summer. Over 1700 staff and kids at daycares in Texas have been infected with COVID since the state’s reopening in late spring, representing a 759% increase since June 15. But we still don’t know the direction of transmission and whether the index cases tended to be staff or kids.

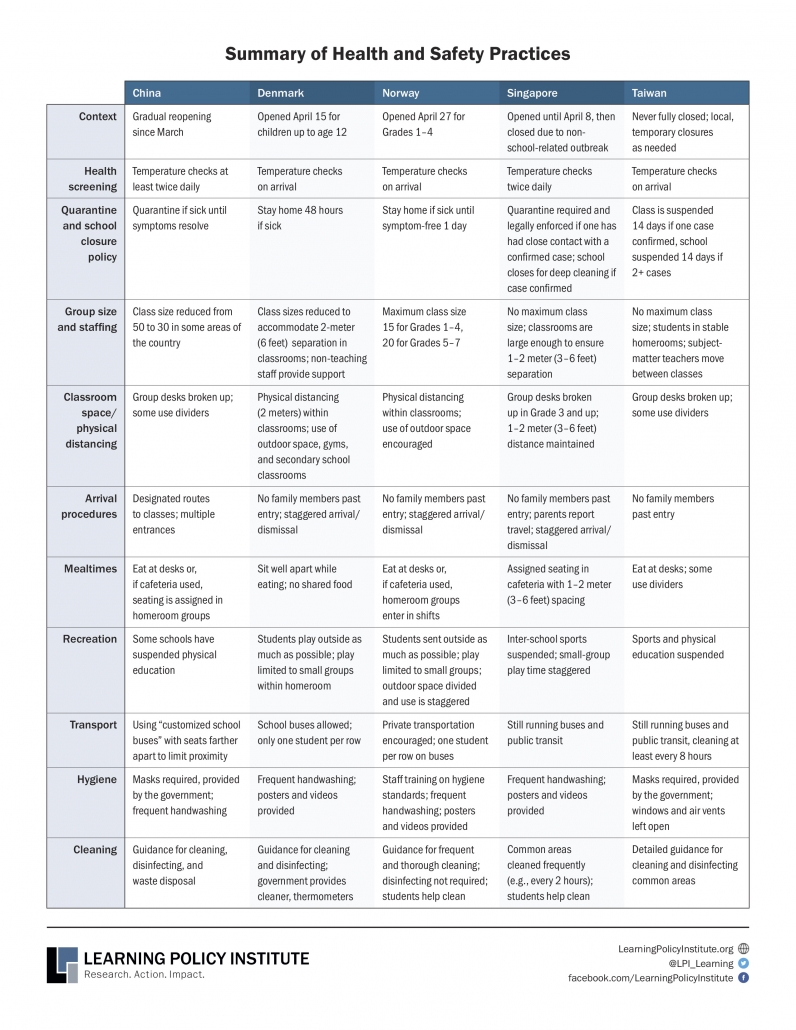

But we should be realistic about what we’re asking of teachers. School administrators and teachers will be working all summer to redesign schools for COVID, following detailed CDC and state and local guidance. But there are enormous logistical hurdles. Even just getting kids to the school is a challenge, especially in cities where school kids take public transit.

It’s critical to recognize that the success of in-person schooling does not fall on the teachers, but the entire community. If we want schools to succeed, we can’t just focus on what happens within a school’s wall. Americans understood the need to social distance to flatten the curve to keep hospitals running. Will they rally around a national strategy to get kids to school? Will Americans start connecting the dots? And recognize that individual decisions about going to a party or wearing a mask impact the downstream likelihood of a five-year old being able to attend kindergarten.

Many US school districts can’t realistically get COVID down to European levels (<1%) by August. What happens in school districts with higher COVID levels will be a grand national experiment. But a collective failing to control COVID this summer means that teachers in areas with high COVID levels may not have a fighting chance this fall. Even magical fairy teachers that can somehow get teenagers to faithfully wear masks and keep 8-year olds six feet apart.

We also need to flexible. Parents may object to a hybrid model of in-person and online education, but this may more realistic in schools districts with higher levels of COVID. Demanding that all schools provide only full-time in-person schooling could backfire by increasing the risk that school outbreaks shutter classrooms entirely. The geographical heterogeneity of COVID in the US means that we need to be particularly flexible and tailor educational strategies specifically to local COVID risk levels. Levels of COVID in a community can change dramatically from week to week, and school districts also need the flexibility to adapt quickly to changing conditions, sometimes preemptively and before the need for change is universally recognized by all members of the community.

TL;DR: America’s grand experiment with opening schools in the middle of a COVID pandemic begins in August. Parents can’t wait. Teachers are wetting themselves. But the experiment could fail quickly if we don’t bring COVID levels down far enough in our communities to avoid school outbreaks and closures.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!