Return of the COVID blog

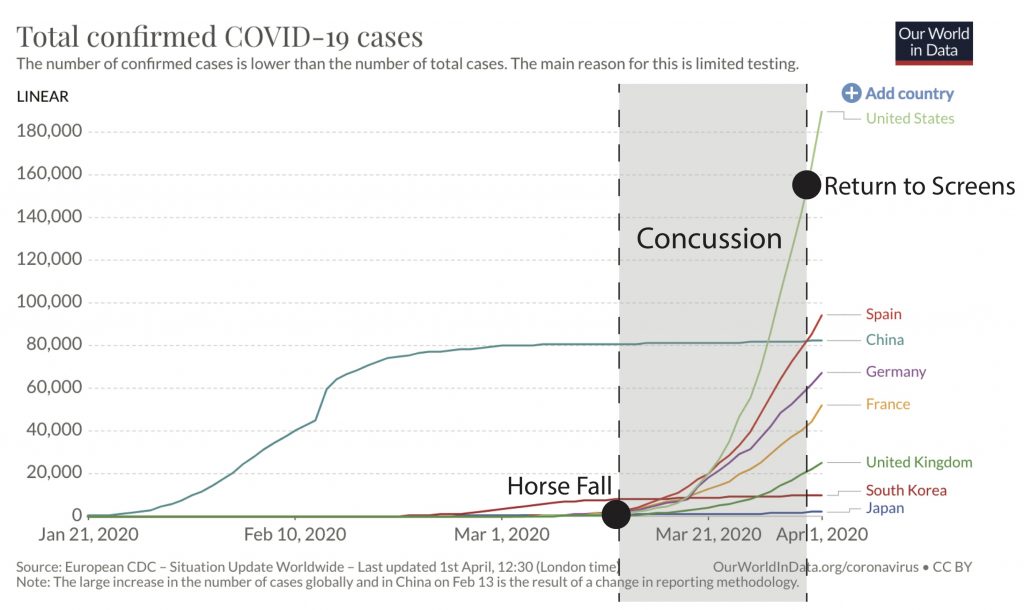

I apologize for the three-week hiatus in the COVID blog. A few Saturdays ago a horse and I had a little disagreement about whether I or not I should be on its back. The horse won. The Suburban Hospital ER was empty except for a few COVID cases, and scans showed that I had experienced a concussion but nothing life-threatening. It was a strange twist of fate that after preparing my entire career for something like COVID, I was suddenly in a brain fog and incapable of viewing screens or even following the COVID situation by radio. For all of you moaning about social distancing, try doing it for a week plus without the distraction of work, Netflix, or cat memes.

So after a three-week semi-dream state I’ve woken up to a brave new world. Some things have stayed the same, including the curious age structure that is mostly sparing children from severe disease. And of course the absence of toilet paper on any store shelves. But in my three-week haze America raced to the top of the global COVID case count. Part of this is increased testing, which we finally seem to have gotten up and running after a botched start. However, I will continually emphasize that the true epidemic is far worse than the case counts and death tallies suggest. We are still massively undercounting cases due to lack of testing. And even the reported death toll is just a fraction of the true number of deaths (which will be statistically calculated, within a certain degree of uncertainty, only after the pandemic is over).

Americans also seem to have all overnight become experts in viral epidemiology. Who imagined a day when droplet transmission and reproductive number would be trending on Twitter? There are some consequences to the proliferation of armchair epidemiologists. The internet has become a cesspool of misinformation. At this moment Americans desperately need reliable information. To know how to stay safe. And to know that they’re tanking their economy for a good reason.

One of the problems is that it can be difficult to evaluate the quality of information, especially on social media. A source of confusion is figuring out who is really an expert. A professor from an eminent US university with a fancy title (e.g., laureate) seems like they should know what they’re talking about. So should a top infectious disease doctor. I can perfectly understand that when COVID is taking over people’s lives there is an irresistible urge for anyone with a loose connection to the biomedical field to weigh in on aspects of COVID. Even in areas far beyond their specific area of expertise. You just make some reasonable assumptions, plug in the little numbers (death rates, attack rates, our favorite reproductive rates), and voila! Anyone can make a pretty graph.

I wish it were so easy to make a good COVID model. I wish we had really good underlying data drawn from intensive testing so we could nail down even simple parameters like rates of mild and asymptomatic infection. Across all age groups so we could know whether children were important in transmission. I wish we had a finely-tuned model that could be more prescriptive about the kinds and intensity of social distancing is needed and for how long. Right now, in the absence of good data, we’re using social distancing as a bludgeon rather than a scalpel. It’s like an elimination diet where you just stop eating everything — gluten, eggs, nuts, dairy — because you don’t know the specific culprit yet.

At this time, we have enough information to know that the situation will be dire if we don’t do anything. That’s not up for debate. But we don’t have a more detailed model that could fine-tune our approach to social distancing. At least not at this late stage in the epidemic (more targeted contact tracing was an option early when the virus was just entering the US but at this stage could not be done without a massively higher intensity of testing). The current unavailability of a good model that can answer our most pressing questions is not because US epidemiologists aren’t any good. There is a relatively small and tight-knit community of experts in the field of mathematical modeling of emerging pathogens. The community has grown over the last decade, as H5N1, Ebola, Zika, and other emerging infectious diseases have increased funding and scientific interest. However, neither H5N1, Ebola, nor Zika every truly invaded America, leading us to become complacent, and major funding networks across the US government for infectious disease modeling have lapsed.

So the list of people who have any business building models to predict the trajectory of COVID-19 would fit no more than a single page. What makes building a COVID model so difficult is how many uncertainties there are, not just about the virus but also human behavior. It doesn’t matter if you’re a professor of epidemiology at an esteemed university or one of the top infectious disease doctors, it takes years of specific study of modeling pathogen dynamics needed to accurately account for these kinds of uncertainties.

Just, to be clear, I am not a modeler. I am an evolutionary biologist who happens to work closely with mathematical modelers. I have great respect for how difficult it is to make a good COVID model. There are enormous gaps in data and information needed to parameterize it. And the parameters are constantly changing as humans modify their behavior. And being a good modeler is a thankless job. Either everyone ignores your model and you fail to help anyone at all. Or politicians take necessary actions and avert a full-scale epidemic, effectively making all your original projections wrong. Which is of course a good thing. But it leaves people with the impression that modelers chronically over-hype.

My area of expertise is how viruses evolve. I’m the person who knocks down the rumors that there are genetically different strains of COVID circulating that cause different severity of disease. Or that the virus will mutate over time to become less lethal and more like a typical cold virus. (It’s quite the reverse. Over the next year or so humans are the ones who will be changing, developing natural or vaccine-induced immunity that makes re-infection less severe. Over the next decade, rather than mutating to become less severe, coronaviruses, like influenza viruses, may continue to evolve to evade human immune responses and cause recurring seasonal epidemics.)

Okay, I’m still limited in my daily allowed screen time. But I want to clear about one final thing that seems to be tripping people up: masks. I am absolutely heartened that so many Americans are willing to don masks to help #flattenthecurve. While it’s been part of Asian culture for a long time to wear a mask when you’re sick, in the West masks are only for doctors, nurses, and Halloween. So, should we imitate the Asians? First off, there is currently a severe shortage of medical-grade masks for doctors and nurses, so if you have a commercially made mask you should donate it instead of wearing it. Even if you’re a risk group. Because the mask cannot protect you, it can only reduce the likelihood of you infecting someone else. Second, if you’re considering making a homemade mask, there’s been a line of thinking that this should be encouraged because keeping your mouth from spewing droplets and infecting other people, and at worst it couldn’t do any harm. But I do think people should be aware of potential harm. An important part of the fight against COVID is training people not to touch their faces. So just be aware that masks that are itchy, uncomfortable, or ill-fitting could actually draw the hand the face, especially for people who aren’t used to wearing them. Or subconsciously give people a false sense of security that emboldened them to do activities they otherwise wouldn’t do without a mask. So it’s not a scientific question, but a human behavior question. But if you’re in a position where you simply can’t follow social distancing at all times (e.g., an essential worker who needs to ride the subway), a mask may be appropriate for a limited time period of commuting. But just keep in mind that the mask is not protecting you.

Hmm, I wanted to finish on a more positive note. I’m going to stretch my screen time a little further to mention something people should do that I don’t think has received as much attention as it deserves. Certainly not compared to masks….. Pre-symptomatic transmission can occur in the days before a person’s first signs of infection (fever, cough, shortness of breath). So if you get a positive test result for COVID, right away you need to inform any people that you had close contact with in the days prior, even before the onset of symptoms, so those people can self-isolate. You should also consider informing people who regularly share surfaces with you know, for example residents in your apartment building. The key is to inform people right away – not days or weeks later.

Taking this another step further, I would even encourage people to let contacts know before you get a test result, as soon as you have been declared a suspected COVID case by your doctor based on symptoms. Many people are still not getting tested, either because they have a mild case or because tests in their area are still unavailable. I understand the desire not to make people unnecessarily anxious, but personally I would rather know if a contact of mine was a suspected COVID case, so I could decide for myself how to act on the information. You could decide to entirely self-isolate if you live with people in risk groups. Or simply postpone going to the grocery store for a period of time.

Most of us are social distancing and hopefully won’t have many contacts. But there are essential workers, whether working in hospitals, grocery stores, or the government, who are still reporting to work, which is why transmission is still occurring. Recognizing the risk for pre-symptomatic transmission and rapidly sharing information about early symptoms and test results with contacts could be a simple, relatively non-draconian way we empower each other to make informed decisions to momentarily intensify our social distancing and potentially break onward transmission of secondary cases.

Summary

- American is experiencing a catastrophic disease event unlike anything we’ve experienced since 1918. The virus is deadly and transmissible.

- Other countries in Asia have demonstrated that an early, aggressive campaign of intensive testing, targeted isolation and contact tracing, and social distancing can dramatically reduce COVID transmission. But America missed that early intervention window and we are now the global epicenter. Ahead is a long period of economic hardship coupled with sickness and death.

- The good news? This is not the new normal. Eventually people will gain immunity, either through natural infection or vaccination. This time next year I am cheerfully optimistic we will be enjoying spring baseball again.

Question for next time: what are the most likely scenarios for the rest of the year?

You as well as the other US experts seem to be at odds with Dr Kim Woo-Ju, the leading expert in South Korea regarding masks. In the interview I recently watched (Asian Boss on YouTube), he believes masks are very important to flattening the curve. He believes part of the issue, besides not having enough masks, is cultural differences. From what I gather he has worked with Dr Fauci.

I agree the effectiveness of wearing masks could vary in different cultural contexts. In regions where people are accustomed to wearing masks regularly, they may be able to wear them without it being a distraction that increases contact between face and hands.

Thanks for this blog, Martha. I didn’t realize you had this up. My comment on this post regards the homemade face mask, too. I watched David Price’s recent video interview on the virus. He opines on the homemade mask, and thinks it could possibly be used to habituate not touching the face. For me, what seems to be working even better are nitrile gloves. I found that the mask fudges with my glasses and creates other small issues which I’m compelled to fix. The rubbery gloves, on the other hand, are a strong reminder to me that my hands are the real issue. I’ve found that my brain can easily (without lengthy adaptation) shun the rubberized hands. I’m curious, though, whether adapting to the gloves would make a return to touching the face possible, whereas an adaptation to the mask would leave you with a barrier to the hands.

Thank you! Your posts are wonderfully written.

Interesting. Changing innate human behaviors is hard, but if people find something that seems to work for them, go for it!

Hi Martha, great to know that you are on the mend and back on your CoviBlog, we look forward to your updates.

I am interested about Antibody-Dependent Enhancement (ADE) and whether it is a factor in the way that Covid can sneak past the immune system of us older persons (OP’s) making it particularly dangerous for us. My limited understanding is that we OP’s have a veritable soup of antibodies from previous viral infections and vaccinations and there is one amongst them that mirrors closely the antibody construct the body needs to combat the Covid-19 virus; close enought that our immune system gets confused about whether or not it has already dealt with this pest and reacts by overproducing the mirror antibody, not the one we need to fight Covid.

I am 68 and my question is: should I still get my seasonal flu jab and add to my antibody soup at this time – despite ADE?

Another matter I’d like your view on is my use of hand sanitiser (HS) to sterilise my lungs. I make my own HS: one part isopropanol to two parts ethanol. I take a small squirt on a hand, rub hands together, bring up to face and breath vapour in through nose – one deep breath only – then in through mouth one deep breath only. As far as I can tell the practice is not fatal 🙂 the effect is a nice clear airway and a wee buzz. Not sure about whether it would nail a Covid but hey.

Thinking of you and your family Martha, warm hugs from down here in NZ where we are all in our home isolation bubbles.

Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) could be an issue for any age group. It happens when antibodies bind to the virus that are not neutralizing. The classic example is dengue. Dengue has 4 serotypes and when you get infected with one you produce antibodies that neutralize that particular serotype, but bind to other serotypes without neutralizing. This can result in hemorrhagic fever, even death. I found a good thread that explains the mechanisms in detail: https://twitter.com/angie_rasmussen/status/1234081358017966080. To my knowledge, ADE occurs between closely related viruses (e.g., DENV-1 and DENV-2), and not between completely different viruses (e.g., CoV and influenza), as flu antibodies wouldn’t be expected to bind to coronaviruses. Aside from ADE, it’s a good idea to get your flu shot since a CoV-influenza co-infection could happen, especially down in New Zealand where the flu season is likely to overlap with your COVID epidemic, and a co-infection could lead to a worse clinical outcome.

Homemade hand sanitizer is a great idea, but I wouldn’t recommend trying to sterilize lungs by inhaling it. The virus is primarily transmitted by the hands.

Is there a way to sign for your blog so we’re notified of new posts?

Any idea when/if widespread antibody testing will happen? I strongly suspect this virus already circulated through my workplace and kids’ school starting in late January. Also, glad you’re on the mend! Really appreciate this blog. It’s great to have a source of accurate, trusted information.

NIH just yesterday announced a trial to study up to 10,000 blood samples for antibodies to COVID. That’s certainly not ‘widespread’ testing but a start.